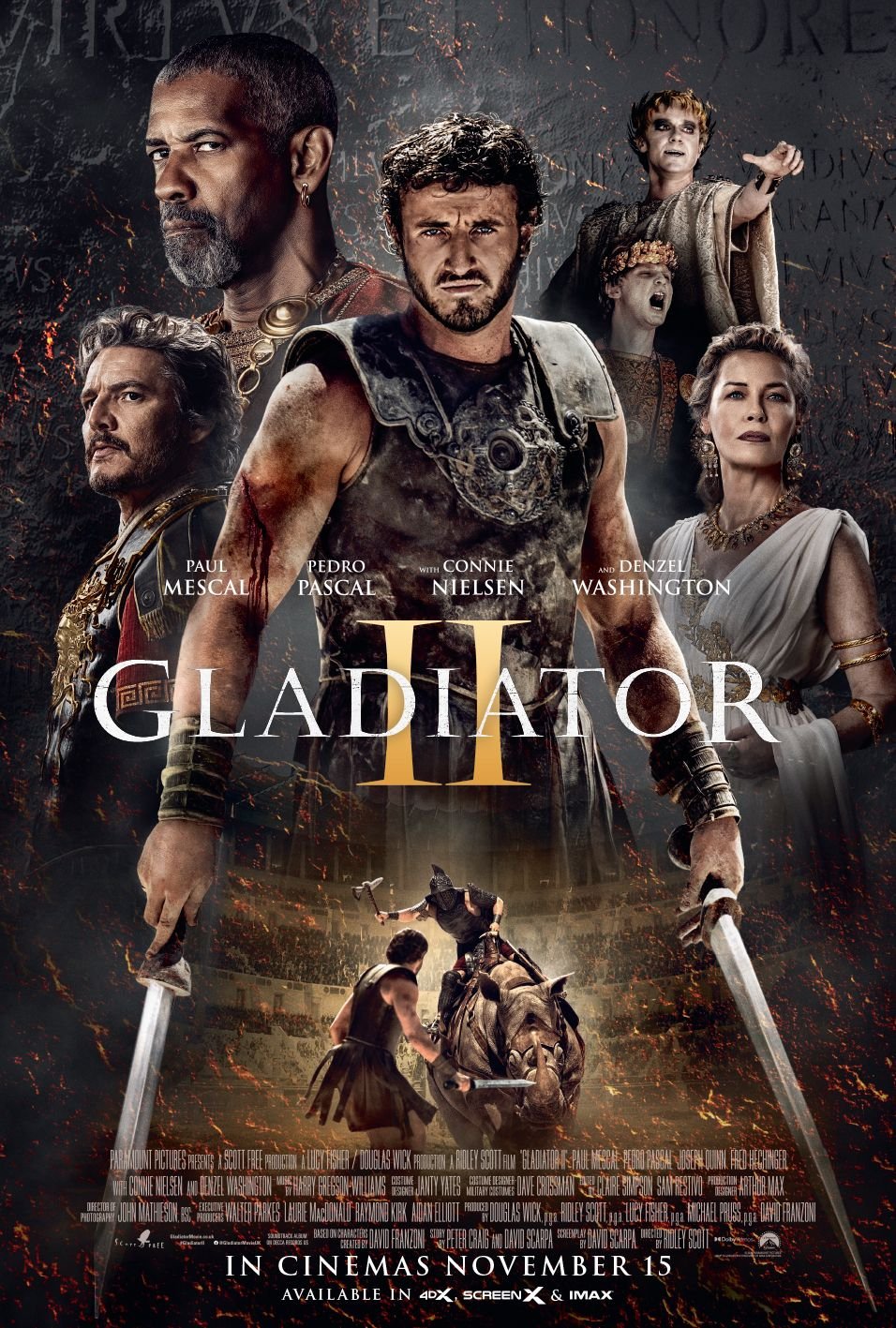

Gladiator II

/Naval combat in the colosseum in Gladiator II

When a trailer for Gladiator II finally appeared back in the summer, I began watching it skeptical and ended it cautiously optimistic. As I laid out here afterward, a sequel to a genuinely great entertainment twenty-four years after the fact seems both unnecessary and ill-advised, and yet the seamless recreation of the original’s feel impressed me. The question, of course, would be whether the finished movie could live up to the promise of its trailer.

Gladiator II begins with Lucius Verus (Paul Mescal) living under an assumed name in North Africa. Flashbacks reveal that his mother Lucilla (Connie Nielsen) sent him into hiding immediately after the events of the first movie, and he now lives in a utopian multiracial coastal community where the men and women cinch up each other’s breastplates and resist the Empire side by side. Shades of Spartacus, perhaps. When the Romans attack with a fleet under the command of Acacius (Pedro Pascal), the city falls, Lucius’s wife is killed, and he is taken captive and sold as a gladiator to the wheeling-and-dealing Macrinus (Denzel Washington). Meanwhile, back in Rome, the disillusioned Acacius reunites with Lucilla, and the two move forward with a plot to overthrow the corrupt and hedonistic co-emperors Geta and Caracalla (Joseph Quinn and Fred Hechinger) during a ten-day sequence of games to be held in honor or Acacius’s victory.

With this relatively simple set of game pieces in place—Lucius wants revenge on Acacius, Acacius wants to overthrow Geta and Caracalla, and Macrinus has a separate agenda of his own—the plot unspools through the added complications of Lucilla’s recognition of Lucius and her and Acacius’s desire to save him from the arena. The increasing unrest in the city and the omnidirectional violence of its politics threaten everyone. Only a few will make it out alive.

Gladiator II is a rousing entertainment, with plenty of spectacle both inside and outside the arena. The action scenes are imaginative, engaging, and well-staged, with the film’s two beast fights—the first a genuinely disturbing bout against baboons in a minor-league arena and another, later, in the Colosseum against a rhinoceros owned by the emperors—being standouts. The scene of naval combat, something I’ve wanted to see ever since learning that the Colosseum could be flooded for that purpose, was another over-the-top highlight, with all the rowing, ramming, spearing, arrow shooting, and burning given just that extra dash of spice by including sharks. Woe to the wounded gladiator who falls overboard. Perhaps even more so than the original, Gladiator II brings you into the excess of Roman bloodsport and the lengths the desensitized will go to for the novel and exciting.

But that is also, notably, the only area in which Gladiator II even matches the original. So, since comparison is inevitable, is Gladiator II as good as Gladiator?

No. The story is more convoluted and takes longer to get into gear, and Paul Mescal’s Lucius, though gifted with genuinely classical features and physical intensity, lacks the instant charisma and quiet interiority of Russell Crowe’s Maximus. His motivation and objectives are also muddled, resulting in his longed-for confrontation with the well-intentioned Acacius feeling less like a tragic collision course and more like an unfortunate misunderstanding. The plot to dethrone the tyrants and restore the Republic feels like a by-the-numbers repeat of the first film’s plot, and the final machinations of Macrinus, in which he uses the jealously between Geta and Caracalla to pit them against each other and unrest in the city to pit the mob against both, though excellently performed by Washington, fizzle out in a final bloody duel outside the city as two armies look on.

I suspect this is what the planned original ending of Gladiator would have felt like had they not rewritten it on the fly after Oliver Reed died. Again, the original was lightning in a bottle, a movie saved by its performances and the improvisatory instincts of talented people. Gladiator II had no such pressures upon it, and though it mimics the scrappy, dusty, smoky look of the original, it lacks the inspired feel of a masterwork completed against the odds. Everything worked smoothly, and the result is less interesting.

As has become my custom with Ridley Scott movies, I have not factored in historical accuracy. No one should. What Scott doesn’t seem to realize is that when you make the conscious artistic decision to depart from the historical record, you should at least make up something good enough to justify the decision. But whenever Scott departs from history he veers immediately into cliche. His Geta and Caracalla are just Caligula knockoffs, and the film’s themes are just warmed-over liberal platitudes. This is Rome-flavored historical pastiche, nothing more. The flavoring makes it immensely enjoyable—speaking as an addict of anything Roman—but actual history has almost no bearing on the movie.

Just one ridiculous example to make my point: in his life under an alias, Lucius marries and settles down in Numidia, where he is close with the leader Jugurtha. It is this peaceful existence that is shattered when Acacius shows up with the Roman fleet and conquers Numidia. Jugurtha and Numidia were real and Jugurtha was defeated by the Romans, adding Numidia to the Empire—in 106 BC. Gladiator II takes place around AD 200. That’s like making something from Queen Anne’s War a plot point in a movie about the American withdrawal from Afghanistan.

But I’m afraid I’ve been unduly harsh. Despite all this, I greatly enjoyed Gladiator II and can’t quite bring myself to fault it for not being the masterpiece that Gladiator is. In addition to the sheer spectacle of the fights and nice callbacks to Maximus, some fun performances help, most especially that by Denzel Washington as Macrinus. Washington plays him with a subtle combination of backslapping bonhomie and cold calculation that makes Macrinus a far more formidable enemy to Lucius and Rome than the dissipated Geta and Carcalla. Lucius is just engaging enough to make a passable hero, but if you see Gladiator II for a performance, see it for Macrinus.

Gladiator II may not have Gladiator’s unique combination of depth and scope, but it has scope in abundance and just enough depth to make it enjoyable, though not moving. As a sequel to the great modern sword-and-sandal epic, Gladiator II is a step down, but as pure entertainment it represents a good afternoon at the movies. I look forward to seeing it again.