Richard Weaver on toughness and heroism

/From Weaver's great Ideas Have Consequences, published in 1948, seventy years ago:

“Since he who longs to achieve does not ask whether the seat is soft or the weather at a pleasant temperature, it is obvious that hardness is a condition of heroism. ”

This passage comes from a chapter entitled "The Spoiled-Child Psychology," in which Weaver documents the degeneration of virtue in the modern world and ascribes our afflictions, crises, and upheavals to an essentially immaturity: a discontent, a raving for a norm of comfort and self-fulfillment that is both unattainable and–the real root of the problem–materialistic. Without the transcendental, an idea he develops later in the same chapter, heroism is meaningless struggle and discomfort. And with the transcendental stripped out of our cultural imagination–so that every human endeavor is nothing but economics, or competition for resources, or, our explanation du jour, simple power–all we can do with the leftovers is squabble like toddlers over the choicest bits.

Richard M. Weaver (1910-63)

I don't entirely agree with some of Weaver's diagnoses. He sees Aristotle as part of the problem, for instance, which is a notion I vehemently disagree with. But few writers have lamented the modern world as thoughtfully or eloquently or with as little hysteria or mordant self-pity as Weaver did in Ideas Have Consequences.

The quotation above, in a bit more of its context. Note Weaver's explicit references to World War II as symptomatic–even on the Allied side:

The trend continues, and in a modern document like the Four Freedoms one sees comfort and security embodied in canons. For the philosophic opposition, that is of course proper, because fascism taught the strenuous life. But others with spiritual aims in mind have taught it too. Emerson made the point: "Heroism, like Plotinus, is almost ashamed of its body. What shall it say, then, to the sugar plums and cat's cradles, to the toilet, compliments, quarrels, cards, and custard, which rack the wit of all human society?" Since he who longs to achieve does not ask whether the seat is soft or the weather at a pleasant temperature, it is obvious that hardness is a condition of heroism. Exertion, self-denial, endurance, these make the hero, but to the spoiled child they connote the evil of nature and the malice of man.

The modern temper is losing the feeling for heroism even in war, which used to afford the supreme theme for celebration of this virtue.

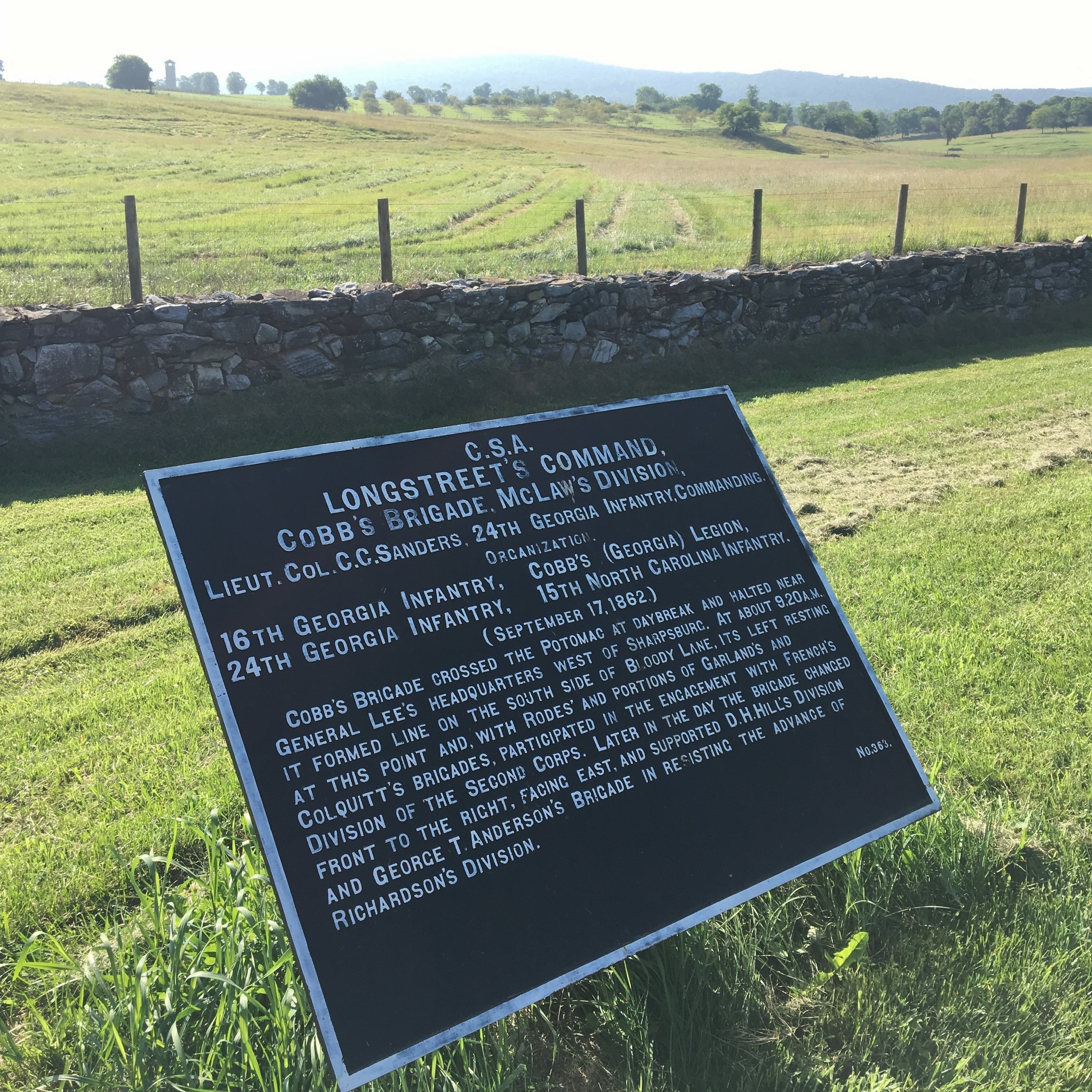

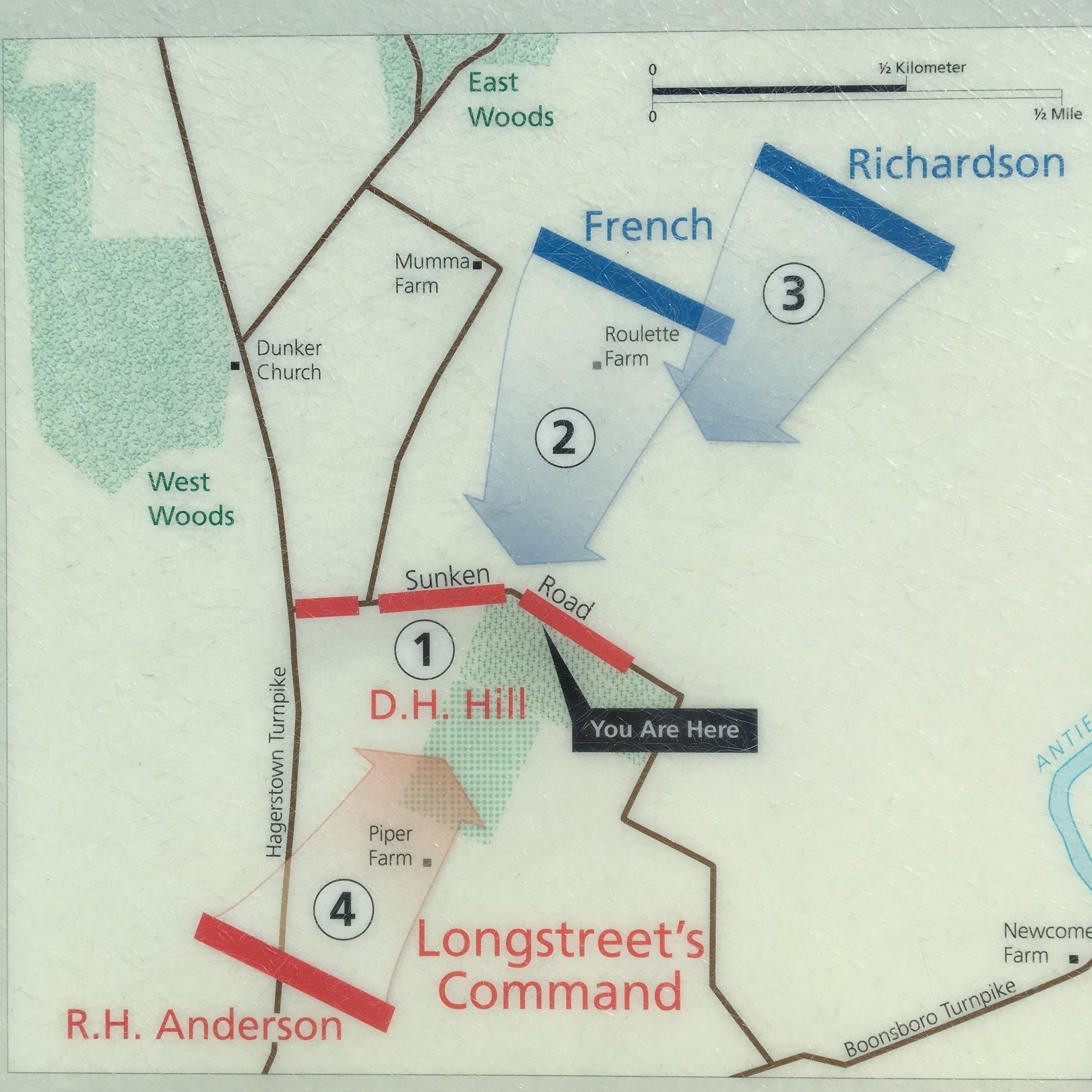

I last read Ideas Have Consequences four or five years ago and have been meaning to reread it since. Do check it out–it's a short, punchy book full of challenging ideas, and it will be well worth your time. Weaver's Southern Essays is also a wonderful collection on a favorite topic of mine, and also worth reading. You will also see a quotation from Weaver as an epigraph to my soon to be released Civil War novel Griswoldville.