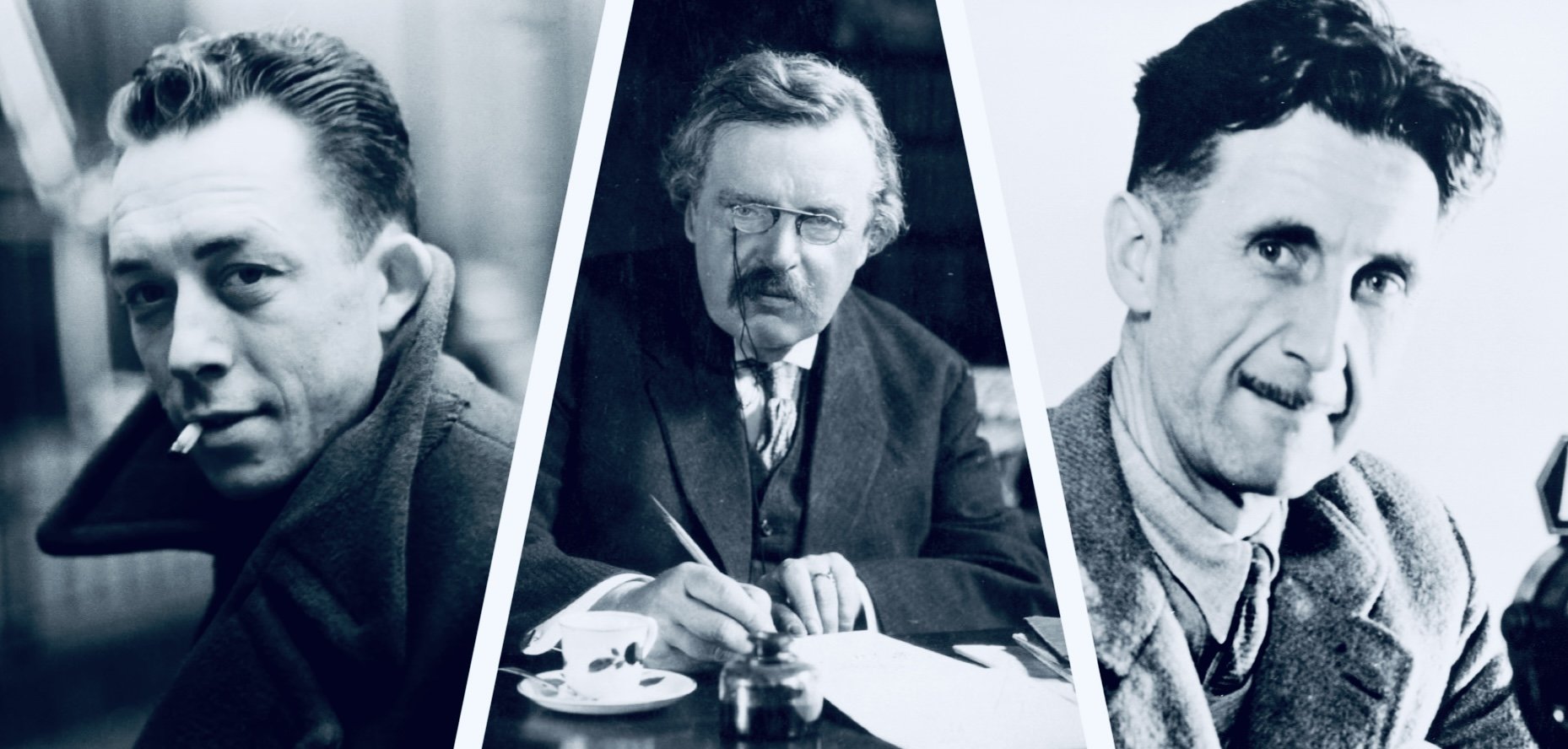

Orwell, Camus, Chesterton, and bad math

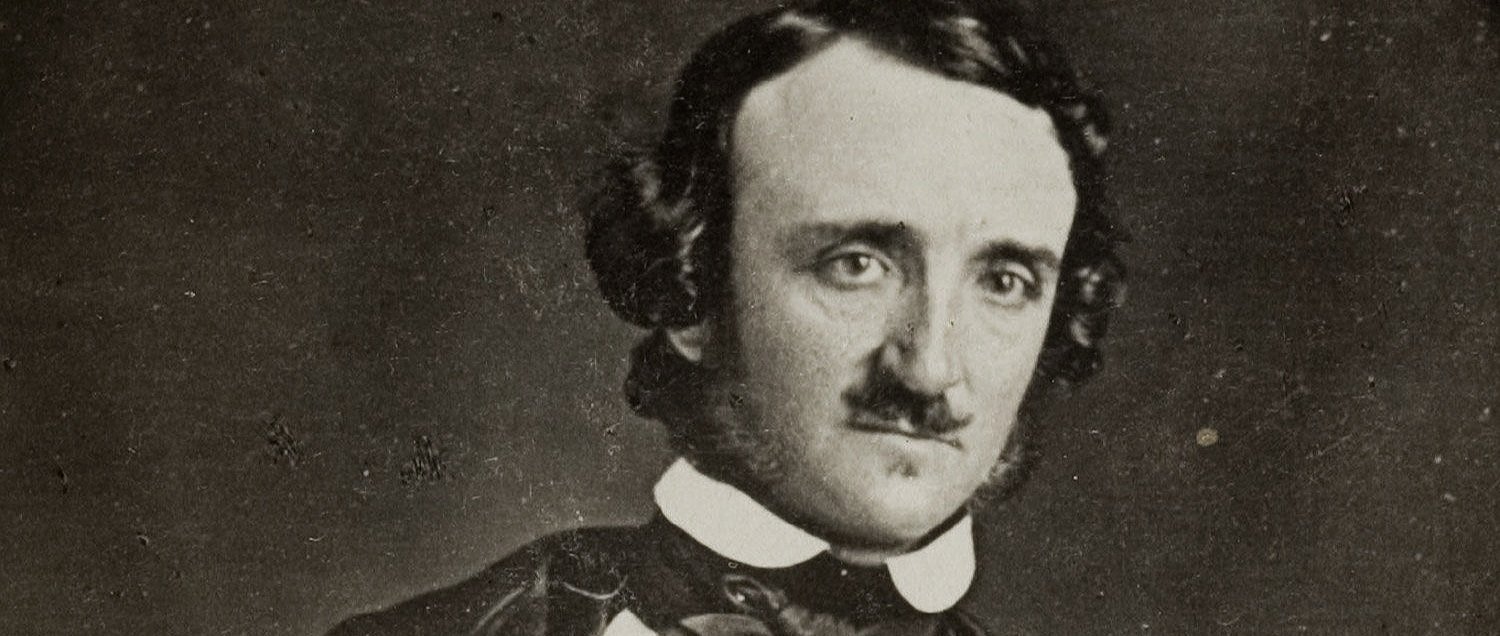

/Earlier this week I read this really interesting piece by William Fear on the most distinctive trait shared by Orwell and Albert Camus: “Both of these writers took the view that truthfulness was more important than ideological allegiance and metaphysics, that the facts should be derived from the real world, rather than the world of ideas.” I can’t weigh in on whether this is true of Camus—I think I read The Stranger and The Plague somewhere around seventeen years ago in college—but it strikes me as a good assessment of Orwell.

Fear uses a particularly striking example to illustrate the closeness of Orwell and Camus’s thought on truth and the threat posed to truthfulness by modern ideology, a major concern for both men—what Fear calls “common ground.” He begins with a line from Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four:

“There comes a time in history when the man who dares to say that two and two make four is punished with death.”

He then points out that, in fact, “these words are not Orwell’s at all. This is a quote from Albert Camus’ novel La Peste, which was published two years before Nineteen Eighty-Four, in 1947.” Fear doesn’t give the exact quotation but this is what I turn up in searching for it:

“But again and again there comes a time in history when the man who dares to say that two and two make four is punished with death. The schoolteacher is well aware of this. And the question is not one of knowing what punishment or reward attends the making of this calculation. The question is one of knowing whether two and two do make four.”

Orwell’s quotation is almost exact, and the import of the quotation—the ideological threat, enforced through peer pressure and naked authority, to admitting what is objectively true and the courage required to do so—is precisely the same. Again, common ground for these writers.

So Orwell got the idea from Camus. But… did Camus get the idea from Orwell? Fear quotes one of Orwell’s book reviews from 1939:

“It is quite possible that we are descending into an age in which two plus two will make five when the Leader says so.”

Fear declines to speculate on precisely whether Camus got this mathematical example from Orwell, noting that the nature of each man’s influence on the other is really beside the point, and continues with his essay. I recommend reading the whole thing.

But a longtime reader of Chesterton cannot read the these three variations on one idea without going back yet further, to a column by GK Chesterton published in the Illustrated London News in 1926. I quote this at greater length because the context makes it clear that the parallel runs deeper than the use of 2+2 as an example:

“We shall soon be in a world in which a man may be howled down for saying that two and two make four.”

But there is not only doubt about mystical things; not even only about moral things. There is most doubt of all about rational things. I do not mean that I feel these doubts, either rational or mystical; but I mean that a sufficient number of modern people feel them to make unanimity an absurd assumption. Reason was self-evident before Pragmatism. Mathematics were self-evident before Einstein. But this scepticism is throwing thousands into a condition of doubt, not about occult but about obvious things. We shall soon be in a world in which a man may be howled down for saying that two and two make four, in which furious party cries will be raised against anybody who says that cows have horns, in which people will persecute the heresy of calling a triangle a three-sided figure, and hang a man for maddening a mob with the news that grass is green.

And this in itself recapitulates something Chesterton wrote as early as his essay collection Heretics, published in 1905. Its stunning final paragraph includes this passage:

The great march of mental destruction will go on. Everything will be denied. Everything will become a creed. It is a reasonable position to deny the stones in the street; it will be a religious dogma to assert them. It is a rational thesis that we are all in a dream; it will be a mystical sanity to say that we are all awake. Fires will be kindled to testify that two and two make four. Swords will be drawn to prove that leaves are green in summer.

So did Orwell get this example from Chesterton? We know Orwell read Chesterton, and that Chesterton even published some of Orwell’s earliest work. So I’d add Chesterton to the lineage of this idea.

But alongside Fear, I’d also say it doesn’t entirely matter. What does matter is the reason Chesterton and Orwell and Camus kept coming back to the childish simplicity of 2+2: an abiding concern for the truth, a truth to be found out there in reality rather than in here in personal perception or political ideology, and a shared—and quite justifiable—anxiety about the threats it faces.

I’ve written before about Orwell’s view of the relation of the modern historical discipline to objective truth, here and here, and about Chesterton and Orwell’s overlapping concerns with language and clarity here. Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni quoted the Heretics version of Chesterton’s line in a clip that went mildly viral—at least among Chesterton fans—several months ago. I still know next to nothing about Camus, largely owing to a prejudicial suspicion of twentieth-century French thinkers, but Fear has convinced me to look again, and more closely.