Summer reading 2024

/Though I’m thankful to say that, compared to where I was at the end of the spring, I’ve wrapped up the summer and begun the fall semester feeling refreshed and rejuvenated, my reading has still been unusually fiction-heavy. That’s not necessarily a bad thing—all work and no play, after all—but I do mean to restore some balance. I look forward to it.

“Summer,” for the purposes of this post, runs from approximately the first week or two of summer classes to today, Labor Day. Since there’s a lot more fiction and non-fiction this time around, I mean to lead off with the smattering of non-fiction reading that I enjoyed. And so, my favorites, presented as usual in no particular order:

Favorite non-fiction

While I only read a handful of non-fiction of any kind—history, biography, philosophy, theology, you name it—almost all of them proved worthwhile. They also make an unusually idiosyncratic list, even for me:

An Illustrated History of UFOs, by Adam Allsuch Boardman—A fun, wonderfully illustrated picture book about UFOs and all sorts of UFO-adjacent phenomena. Not deep by any means and only nominally skeptical, this book is surprisingly thorough, with infographic-style tables of dozens of different purported kinds of craft, aliens both cinematic and purportedly real, and brief accounts of some legendary incidents from Kenneth Arnold and the Roswell crash to Betty and Barney Hill’s abduction, Whitley Strieber’s interdimensional communion, and the USS Nimitz’s “flying Tic Tac.” If you grew up terrified to watch “Unsolved Mysteries” but also wouldn’t think of missing it, this should be a fun read. See here for a few sample illustrations.

Histories and Fallacies: Problems Faced in the Writing of History, by Carl Trueman—A concise, sensible, and welcoming guide to some of the pitfalls of historical research and writing. Trueman is especially good on the dangers of historical theories, which naturally incline the historian to distort his evidence the better to fit the theory. There are more thorough or exhaustive books on this topic but this is the one I’d first recommend to a beginning student of history. I mentioned it prominently in my essay on historiography at Miller’s Book Review back in July.

Three Philosophies of Life, by Peter Kreeft—A short, poetic meditation on three Old Testament wisdom books: Ecclesiastes and Job, two of my favorite books of the Bible, and Song of Songs, a book that has puzzled me for years. Kreeft presents them as clear-eyed dramatizations of three worldviews, the first two of which correctly observe that life is vain and full of suffering, with the last supplying the missing element that adds meaning to vanity and redemption to pain: God’s love. An insightful and encouraging short book.

Homer and His Iliad, by Robin Lane Fox—Who was Homer and what can we know about him? Was he even a real person? And what’s so great about his greatest poem? This is a wide-ranging, deeply researched, and well-timed expert examination of the Iliad and its author, thoroughly and convincingly argued. Perhaps the best thing I can say about Lane Fox’s book is that it made me fervently want to reread the Iliad. My favorite non-fiction read of the summer. Full-length review forthcoming.

Always Going On, by Tim Powers—A short autobiographical essay with personal stories, reminiscences of Philip K Dick, nuts and bolts writing advice, aesthetic observations, and philosophical meditations drawing from Chesterton and CS Lewis, among others. An inspiring short read.

The Decline of the Novel, by Joseph Bottum—An excellent set of literary essays on the history of the novel in the English-speaking world; case studies of Sir Walter Scott, Dickens, Thomas Mann (German outlier), and Tom Wolfe; and a closing meditation on popular genre fiction—all of which is only marginally affected by a compellingly argued but unconvincing thesis. I can’t emphasize enough how good those four case study chapters are, though, especially the one on Dickens. Full dual review alongside Joseph Epstein’s The Novel, Who Needs It? on the blog here.

Favorite fiction

Again, this was a fiction-heavy summer in an already fiction-heavy year, which was great for me while reading but should have made picking favorites from the long list of reads more difficult. Fortunately there were clear standouts, any of which I’d recommend:

On Stranger Tides, by Tim Powers—An uncommonly rich historical fantasy set in the early years of the 18th century in the Caribbean, where the unseen forces behind the new world are still strong enough to be felt and, with the right methods, used by new arrivals from Europe. Chief among these is Jack Chandagnac, a former traveling puppeteer who has learned that a dishonest uncle has cheated him and his late father of a Jamaican fortune. After a run-in with seemingly invincible pirates, Jack is inducted into their arcane world as “Jack Shandy” and slowly begins to master their arts—and not just knot-tying and seamanship. A beautiful young woman menaced by her own deranged father, a trip to Florida and the genuinely otherworldly Fountain of Youth, ships crewed by the undead, and Blackbeard himself further complicate the story. I thoroughly enjoyed On Stranger Tides and was recommending it before I was even finished. That I read it during a trip to St Augustine, where there are plenty of little mementos of Spanish exploration and piracy, only enriched my reading.

Journey Into Fear, by Eric Ambler—An unassuming commercial traveler boards a ship in Istanbul and finds himself the target of a German assassination plot. Who is trying to kill him, why, and will he be able to make it to port quickly enough to survive? As much as I loved The Mask of Dimitrios back in the spring, Journey into Fear is leaner, tighter, and more suspenseful. A wonderfully thrilling read.

The Kraken Wakes, by John Wyndham—Another brilliant classic by Wyndham, an alien invasion novel in which we never meet or communicate with the aliens and the human race always feels a step behind. Genuinely thrilling and frightening. Full review on the blog here.

Mexico Set, by Len Deighton—The second installment of Deighton’s Game, Set, Match trilogy after Berlin Game, this novel follows British agent Bernard Samson through an especially tricky mission to Mexico City and back as he tries to “enroll” a disgruntled KGB agent with ties to an important British defector. Along with some good globetrotting—including scenes in Mexico reminiscent of the world of Charles Portis’s Gringos—and a lot of tradecraft and intra-agency squabbling and backstabbing, I especially appreciated the more character-driven elements of this novel, which help make it not only a sequel but a fresh expansion of the story begun in Berlin Game. Looking forward to London Match, which I intend to get to before the end of the year.

LaBrava, by Elmore Leonard—A former Secret Service agent turned Miami photographer finds himself entangled in an elaborate blackmail scheme. The mark: a former Hollywood femme fatale, coincidentally his childhood favorite actress. The blackmailers: a Cuban exile, a Florida cracker the size of a linebacker, and an unknown puppet master. Complications: galore. Smoothly written and intricately plotted, with a vividly evoked big-city setting and some nice surprises in the second half of the book, this is almost the Platonic ideal of a Leonard crime novel, and I’d rank only Rum Punch and the incomparable Freaky Deaky above it.

Night at the Crossroads, by Georges Simenon, trans. Linda Coverdale—Two cars are stolen from French country houses at a lonely crossroads and are returned to the wrong garages. When found, one has a dead diamond smuggler behind the wheel. It’s up to an increasingly frustrated Inspector Maigret to sort through the lies and confusion and figure out what happened. An intricate short mystery that I don’t want to say much more about, as I hesitate to give anything at all away.

Epitaph for a Spy, by Eric Ambler—A stateless man spending some hard-earned cash at a Riviera hotel is, through a simple mix-up, arrested as a German spy. When the French police realize his predicament and his need to fast-track his appeal for citizenship, they decide to use him to flush out the real spy. Well-plotted, suspenseful, and surprising, with a great cast of characters. My favorite Ambler thriller so far this year. There’s also an excellent two-hour BBC radio play based on the book, which Sarah and I enjoyed on our drive back from St Augustine.

The Light of Day, by Eric Ambler—One more by Ambler, which I also enjoyed. Arthur Simpson, a half-English, half-Egyptian smalltime hood involved in everything from conducting tours without a license to smuggling pornography is forced to help a band of suspicious characters drive a car across the Turkish border. He’s caught—and forced to help Turkish military intelligence find out what the group is up to. Published later in Ambler’s long career, The Light of Day is somewhat edgier, but also funnier. It’s more of a romp than a heavy spy thriller, with wonderfully sly narration by Arthur himself. I greatly enjoyed it. Do yourself a favor, though, and read it without looking at any summaries, even the one on the back of the book. My Penguin Modern Classics paperback gave away a major plot revelation. I still enjoyed it, but have to wonder how much more I might have with that important surprise left concealed.

Runner up:

Swamp Story, by Dave Barry—A wacky crime novel involving brothers who own a worthless Everglades bait shop, potheads trying to make their break into the world of reality TV, a disgraced Miami Herald reporter turned birthday party entertainer, a crooked businessman, Russian mobsters, gold-hunting ex-cons, and a put-upon new mom who finds herself trying to survive all of them. Fun and diverting but not especially funny, which some of Barry’s other crime thrillers have managed to be despite going darker, I still enjoyed reading it.

John Buchan June

The third annual John Buchan June included five novels, a short literary biography of one of Buchan’s heroes, and Buchan’s posthumously published memoirs. Here’s a complete list with links to my reviews here on the blog:

Castle Gay (1930)

Salute to Adventurers (1915)

The Free Fishers (1934)

The Island of Sheep (1936)

The House of the Four Winds (1935)

Memory Hold-the-Door (1940)

Of this selection, my favorite was almost certainly The Free Fishers, a vividly imagined and perfectly paced historical adventure with a nicely drawn and surprising cast of characters. “Rollicking” is the word Ursula Buchan uses to describe it in her biography. An apt word for a wonderfully fun book. A runner up would be Salute to Adventurers, an earlier, Robert Louis Stevenson-style tale set in colonial Virginia.

Rereads

I revisited fewer old favorites this season than previously, but all of those that I did were good. As usual, audiobook “reads” are marked with an asterisk.

Casino Royale, by Ian Fleming—Subject of this blog post on Fleming’s poetic attention to rhythm.

The Whipping Boy, by Sid Fleischman—Read aloud to the kids this time. They greatly enjoyed it.

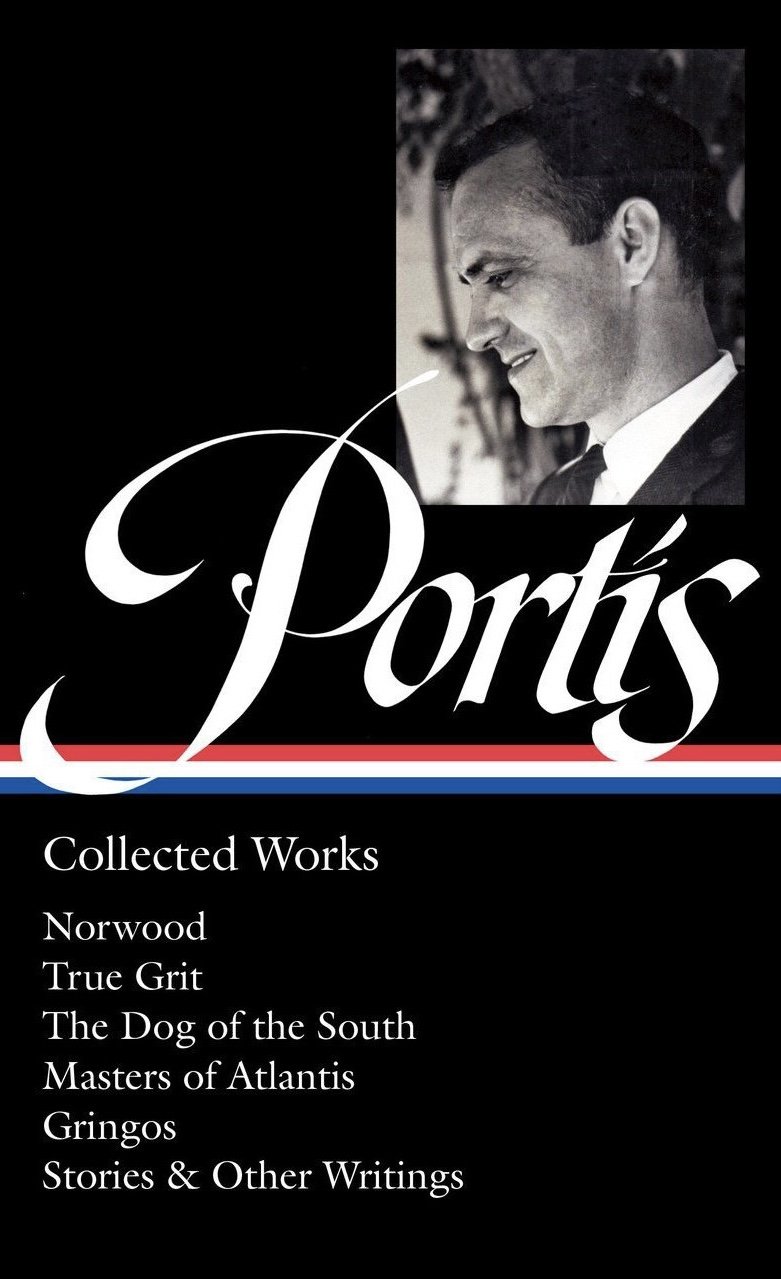

Masters of Atlantis, by Charles Portis*—Subject of this blog post about the petty indignities that Portis repeatedly inflicts on his characters, what the kids call “cringe humor” nowadays.

Conclusion

I’m looking forward to more good reading this fall, including working more heavy non-fiction back into my lineup as I settle into the semester. I’m also already enjoying a couple of classic rereads: Pride and Prejudice, which I’ve been reading out loud to my wife before bed since early June, and Shadi Bartsch’s new translation of the Aeneid. And, of course, there will be fiction, and plenty of it.

I hope my summer reading provides something good for y’all to read this fall. As always, thanks for reading!