After-action report: 16th International Conference on World War II

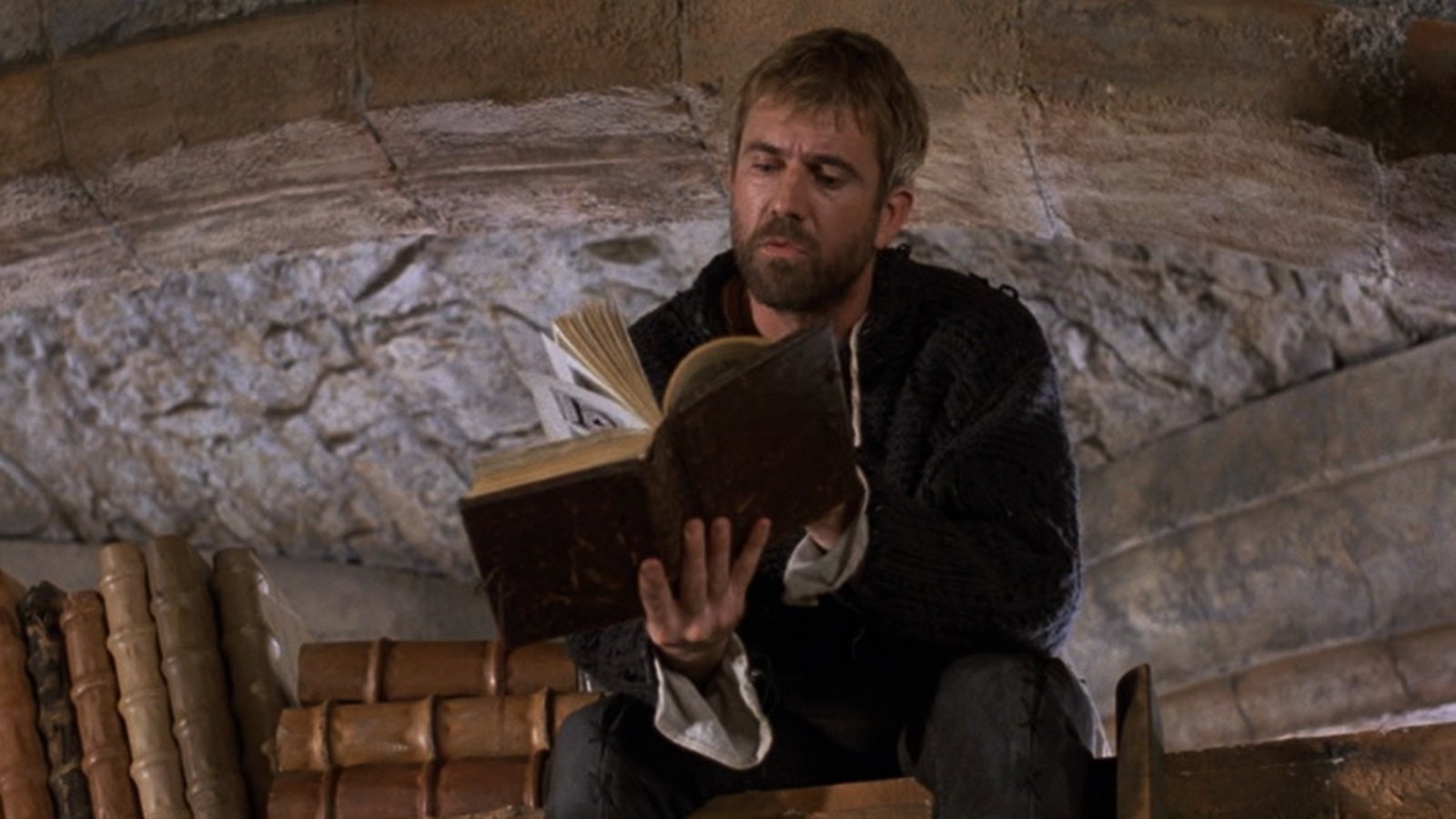

/An M4 Sherman of the 14th Armored Division crashes through the fence of the POW camp at Hammelburg, April 1945

Last weekend was the annual International Conference on World War II at the National WWII Museum in New Orleans. Learning last year—thanks to my friend and colleague Kirk at another college here in South Carolina—that online attendance was free was a major discovery, and this is the second year I’ve been able to tune in from afar.

As I alluded to in my last post, I’ve been sick all week, and though I began with grand intentions to read a lot, catch up on my significant backlog of correspondence, and publish several blog posts that have been simmering in draft form, pretty much all I’ve been able to do is lie in bed and read. I even started to go through my drafts folder deleting partially completed posts that I now deemed irrelevant, but just before I clicked delete on this one I took one more look at my outline and the few synopses I had already written.

I’m glad I did. I decided to buckle down and finish writing these up these, because the conference was excellent and I found blogging about it helpful last year. I hope these brief summaries will be helpful to y’all, too, and that you’ll seek out the recordings of these sessions at the museum’s Vimeo channel.

Thursday, December 7—Pre-conference symposium

The theme of Thursday’s pre-conference symposium was Finding Hope in a World Destroyed: Liberations and Legacies of World War II. The panel discussions therefore primarily focused on things happening immediately after the war or caused by the war rather than the war itself.

Europe in the Rubble, chaired by Jason Dawsey, panelists Robert Hutchinson and Gunter Bischof

A good opening session that paid particular attention to war crimes trials and sentencing. Dawsey outlined Soviet participation in—and manipulation of—the international war crimes trials at Nuremberg as well as the way Soviet concepts like “crimes against peace” have made their way into present-day intellectual norms. Hutchinson, in an especially interesting talk, discussed the often naïve ways American war crimes prosecutors, in the interests of fairness and with the goal of a kind of universalist liberal pedagogy, modeled their sentencing, appeals processes, and standards of “rehabilitation” for former Nazis on the American judicial system. The concept of the Nuremberg trials as “liberal show trials” that were meant, like Soviet show trials, to instruct observers was enlightening. Bischof’s talk briefly covered some major aspects of the Marshall Plan, including its popularity in Austria and the devastating results for Soviet-occupied countries of Soviet refusal to participate.

Books recommended: After Nuremberg: American Clemency for Nazi War Criminals, by Robert Hutchinson

Aftermath in Asia, chaired by John Curatola, panelists Yuma Totani and Rana Mitter

An opening talk on the eventual adoption by Japan of democracy and Western-style concepts of rights and equality as Douglas MacArthur’s greatest victory was somewhat interesting, though I have read enough Yukio Mishima to be suspicious of the supposed benefits of the Westernization, democracy, and capitalism imposed upon the Japanese. The second talk, on the trial and punishment of Japanese war criminals, began with some odd finger-pointing at Russia and the United States (over the invasion of Ukraine and the detention of terrorists at Guantánamo Bay, presumably, though this was not totally clear) as examples of moral failure before moving on to a very hard-to-follow narrative of Japan’s war crimes trials—which, knowing what kind of brutality the Japanese got up to during the war, makes the opening remarks seem silly by comparison. I struggled to follow this one.

The real draw for me was Rana Mitter, whom I have heard on The Rest is History and who always presents his work with enviable enthusiasm and mastery of the material. He didn’t disappoint. His talk on the role of China during the war was excellent, especially his attention to Chiang Kai-shek’s participation in the Cairo Conference, the subsequent reversal of what he accomplished there by the Soviets at Tehran just a few days later, and the lingering relevance of the war in modern China, which still uses the Cairo Declaration as grounds for claiming islands in the South China Sea, for example.

Follow-up Q&A for this one was more interesting, with one audience member asking pretty bluntly whether Emperor Hirohito should have stood trial for war crimes (Totani’s answer: “Yes”) and another describing how his elderly Chinese neighbor, who grew up during the war, is “adamant” that no one gave help to China because of the sheer number of funerals she remembers then.

Books recommended: Forgotten Ally: China’s World War II, 1937-1945, by Rana Mitter

A New World Order and Postwar US Responsibilities, chaired by William Hitchcock, panelists Blanche Wiesen Cook, Jeremi Suri, and Lizabeth Cohen

I found myself thinking of this one as “the liberal panel” in the sense of the sentimental, do-good liberalism of FDR. Indeed, the first talk was from a senior scholar of Eleanor Roosevelt and covered Mrs Roosevelt’s involvement in the development of the postwar UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights. As befit its subject, it was full of gassy positivity about equality and abstract political and social rights as well as gentle, disapproving shock that the US has still not signed onto some of the Declaration’s economic provisions. The third talk was an expert discussion of the ideals and, of course, the failures of “the consumer republic” created by the postwar economic boom, suburbanization, GI Bill education, and so forth, with a heavy emphasis on the failures, exclusions, and inequalities that persisted or were purportedly worsened as a result. You can read precisely the same yes-but approach to 1950s prosperity in the textbook I used for US History II this fall.

The panel ended with the chair suggesting a major lesson of the war was the power of the federal government to solve problems if it were only allowed to grow to the size necessary to handle them, as well as a breathless discussion of “the war on education” being waged in the US right now, with the first panelist admitting she hadn’t looked into its causes but still disapproved. I’d mildly suggest finding out why people are upset and what specifically they’re upset about before dismissing them as waging war on something as abstract as “education.”

However, the second of the three talks, by Jeremi Suri, was a masterful explanation of the quiet political revolution the United States underwent as a result of the war. Suri clearly laid out the ways participation in the war caused a massive extraconstitutional—and often unconstitutional—shift in the way the US government approached foreign policy and the military. The result was a country that began the 20th century with a mostly isolationist stance, an entrenched tradition of a small peacetime army made up of volunteers, and tight congressional controls on warmaking ended the 20th century entangled in the whole world’s affairs, maintaining vast alliances and with troops deployed to dozens of countries, and an enormous military under almost unchecked executive control. This was an excellent short talk and I hope to either assign it or play it in class for future sections of US History II.

We Shall Overcome: From Wartime Service to Social Change, chaired by Steph Hinnershitz, panelists Marcus Cox, Kara Vuic, and David Davis

Unfortunately I was only able to catch the first of the panelists, Marcus Cox, but he gave an exceptionally interesting talk on the challenges and, especially, the opportunities armed service during World War II presented to African-American men. He began with a moving personal reflection on his own grandfather’s US Army career from 1941 to retirement in 1972 and ended with brief snapshots of the roles played in the civil rights movement by black WWII veterans. A strong, worthwhile talk.

Rethinking World War II, Gen Raymond E Mason Jr Distinguished Lecture on World War II, Jeremy Black and Rob Citino

A very good freeform chat ranging across a variety of topics but concentrating mostly on the scale and scope of the war as well as some of its legacies. Black is by some measures the most published historian in the world (he publishes an average of about four books per year; here’s one I reviewed a couple years ago) and an expert on strategy. He had plenty to say on that not only from a theatre but a global perspective—some of his discussion of Japan, China, and the East dovetailed nicely with Mitter’s talk earlier in the day—as well as more nitty-gritty topics. Black is also, like Citino, his interlocutor in this discussion, funny and engaging as well as an expert who can always add more, making them well-matched and enjoyable to listen to. (“Easiest interview ever,” Citino joked at the end of the talk.)

Books recommended: Military Strategy: A Global History, A History of the Second World War in 100 Maps, and Air Power: A Global History, by Jeremy Black

Friday, December 8

Nimitz and His Commanders: Leadership in the PTO, roundtable discussion chaired by Jonathan Parshall, panelists Craig L Symonds and Trent Hone

A good discussion, based on Symonds’s book, of the character and leadership of Admiral Nimitz and the challenges he faced in his role as the Commander in Chief of the US Pacific Fleet from after Pearl Harbor to the end of the war. One especially interesting topic was Nimitz’s Eisenhower-like ability to get difficult subordinates to work together.

Books recommended: Nimitz at War: Command Leadership from Pearl Harbor to Tokyo Bay, by Craig L Symonds

In the Rubble, roundtable discussion moderated by Allan R Millett, panelists Keith Lowe and Donald Bishop

I was especially keen to listen to this discussion since Lowe’s Savage Continent strongly affected my understanding of the end and outcomes of the war when I read it about ten years ago. Both Lowe and fellow panelist Bishop, who primarily focused on Asia, were excellent, explaining graphically but dispassionately both the immediate challenges facing those left in the rubble—disease, starvation, homelessness, prostitution, rape—as well as longer-term problems like the plight of DPs (displaced persons), many of whom languished in camps for years. Lowe also discussed the often-overlooked ethnic cleansing that took place throughout Eastern Europe at the end of the war—at the same time the Soviets were violently suppressing native opposition in order to install puppet regimes—with millions of Germans from historically ethnically mixed regions of Poland, the Baltic, and Czechoslovakia either murdered or driven out, actions that caused the deaths of millions more Germans even after the war’s end. Lowe in particular was able to draw on conversations with a survivor of the aftermath for striking and poignant anecdotes.

Books recommended: A Continent Erupts: Decolonization, Civil War, and Massacre in Postwar Asia, 1945-1955, by Ronald Spector, Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II, by Keith Lowe, War Trash, by Ha Jin

To the End of the Earth: The US Army and the Downfall of Japan, 1945, John C McManus in conversation with Conrad Crane

Another good book-based discussion, this one based on the recent final volume of McManus’s trilogy covering the US Army’s role in the Pacific Theatre, which is popularly associated more with the Navy and Marines. (I have the first volume, Fire and Fortitude, but haven’t read the entire book yet.) Some discussion of New Guinea, the Philippines, and Okinawa.

Books recommended: McManus’s US Army in the Pacific trilogy, Fire and Fortitude: The US Army in the Pacific War, 1941-1943, Island Infernos: The US Army’s Pacific War Odyssey, 1944, and To the End of the Earth: The US Army and the Downfall of Japan, 1945.

Missed sessions:

Our War, Too! chaired by Steph Hinnershitz, panelists Catherine Musemeche, Dave Gutierrez, and James C McNaughton

Legacies of World War II, chaired by Gordon H “Nick” Mueller, panelists William Hitchcock and Jeremi Suri

Saturday, December 9

Dauntless: Paul Hilliard in World War II, WWII veteran Paul Hilliard in conversation with Rob Citino

Last year the Museum hosted centenarian veteran John “Lucky” Luckadoo, a B-17 pilot who flew 25 missions over Europe. This year the younger—at age 98!—Paul Hilliard gave a talk about his experience as a Marine dive bomber pilot in the Pacific. He also talked about growing up a Wisconsin farm boy and how, despite the Depression, he was largely unaware that his family was poor (“When you’re born on the floor you don’t spend a lot of time worrying about falling out of bed.”) Especially touching was his memory of the train ride from Wisconsin to California when he joined the Marines; he didn’t sleep for three days as he watched the magnificent American landscape roll past his window. After the war he went to college and wound up, through an odd series of circumstances, in the oil business, which settled him in New Orleans, where he has practiced philanthropy toward the WWII Museum, an art museum, and other institutions for decades. I greatly enjoyed Hilliard’s talk, especially since, with his genuine rags to riches story, toughness, and hard work coupled with good humor, he reminded me so much of my granddad.

Books recommended: Dauntless: Paul Hilliard in World War II and a Transformed America, by Rob Citino, Ken Stickney, and Lori Ochsner

Monuments Men and Women: A Never-Ending Story, with Robert M Edsel

The most flat-out enjoyable session of the conference. Edsel is a businessman who first became interested in art preservation during a trip to Italy. Wondering how it was that local people managed to preserve their artistic and architectural treasures during the most destructive war in history, few people were able to offer him answers. He set out to learn for himself. The result was several books, including The Monuments Men, the basis of the George Clooney film ten years ago, and The Monuments Men and Women Foundation, which Edsel helped establish. The MMWF exists to promote the memory of the people, mostly middle-aged academics with no military experience, who worked with troops on the frontlines to protect, recover, and return artwork stolen by the Nazis during the war. It also actively seeks lost artwork—there are still millions of works unaccounted for from the war—for restitution and has worked with the US military to reestablish a unit dedicated to art protection in war zones.

Edsel spoke with great passion as he told the story of the original monuments men—a much larger group and who worked for far longer than the Clooney film could convey—and the work of his foundation. He briefly described the careers of some important members of the unit, as well as the handful who were killed or wounded in action as part of their work. He also told some especially interesting and even moving stories about works of art either stolen by the Nazis or simply taken as souvenirs by GIs at the end of the war being restored to their rightful owners many decades after the war.

But I was most moved by Edsel’s passionate advocacy of the place of art in the memories and souls of people. In an age of ideologically-motivated vandalism and destruction of art, in which crowds cheer the toppling of statues and activists destroy paintings in the name of political platforms, to hear someone speak up so forcefully on behalf of preservation in the name of the dead and for future generations was more refreshing than I can express.

Books recommended: The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves, and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History, which is the basis of the film The Monuments Men, directed by George Clooney, Rescuing Da Vinci, and Saving Italy: The Race to Rescue a Nation’s Treasures from the Nazis, by Robert M Edsel

Mass Murder and Memory in Eastern Europe, the George P Shultz Forum on World Affairs, Christopher Browning in conversation with Alexandra Richie

A grim but outstandingly good discussion. Richie was one of my favorite panelists last year, when she covered the 1944 Warsaw Uprising among other things, so I was excited to hear her talk with the great historian Christopher Browning. They focused primarily on Browning’s classic study Ordinary Men, which examined the role played by a single battalion of reservist military policemen in killing tens of thousands of Jews in one region of Nazi-occupied Poland during the first phase of the Holocaust, when local populations were shot in batches rather than shipped to extermination camps. Browning and Richie walked through the book’s major points—that the reservists in question were not die-hard Nazis but middle-aged, bourgeois types, that there was no penalty for refusing to participate in the killings, that most of them participated in the beginning and all of them participated by the end.

Richie and Browning also discussed some of the aspects of social psychology he used to understand—rather than explain—how these men, who were neither Nazis nor psychopaths, could do what they did, including the Milgram tests, which found that physical and psychological distance were key factors in enabling the maximum infliction of suffering on other people at the behest of authority, and the Stanford prison experiment. They also helpfully talked through some of the controversies about methodology and interpretation surrounding the book.

I routinely recommend Ordinary Men when I teach World War II in class and will certainly use or assign this one-hour talk in the future, offering as it does a succinct but still chilling summary of the book’s themes, the most important of which is the challenging truth that there’s not as much difference between mass killers like these and ourselves as we’d like to think.

Books recommended: Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland, by Christopher Browning

Missed sessions:

Forgotten Heroes, chaired by Jeffrey Sammons, panelists Maj Gen Peter Gravett and Cameron McCoy

General Lesley J McNair: Unsung Architect of the US Army, Mark Calhoun in conversation with John C McManus

Conclusion

I was able to catch a majority of the conference sessions this year, and it was exceptionally rewarding. I’m grateful again to the National WWII Museum for hosting this event and making it available to attend online for free. Their hard work in educating the public and remembering the war and the men who fought it is, I hope, paying off. I’m certainly looking forward to next year.

Thanks for reading! I hope this has been helpful to you and that you’ll check out some of these sessions online as well as some of the books mentioned during the conference.