I struggle to describe it myself. There is no one word for it. I’ve seen people describe it as cold or inhuman. These are flatly wrong, and critics who describe the book this way are usually assuming something about Jünger personally and projecting that onto the book. Dispassionate suggests itself, though Jünger describes plenty of high emotion, from elation to terror, and even describes himself weeping on multiple occasions.

Perhaps the best word is forthright. Jünger’s narration and descriptions, analytically observed and cataloged with his entomologist’s eye,** are bracingly, disturbingly forthright. He tells but does not explain, much less praise or condemn. These concerns lie outside his purpose, which is to relate what he lived through and what it was like. And he narrates everything in the book with the same unflappable forthrightness, whether his rookie mistakes on sentry duty, the miserable conditions of trench life, the joy of finding an abandoned store of wine, the variety and effects of British and French grenades, the corpses of the dead, the death of a little girl killed by British shrapnel, the excitement of going over the top, the terror of hand-to-hand combat, the experience of being hit by shell fragments, caught in barbed wire, shot through the chest.

All of these are narrated so bluntly, so matter-of-factly, that they seem to need no literary adornment, though Jünger was a skilled craftsman and carefully worked over his diaries to produce this book. The result is uniquely horrifying—and thrilling.

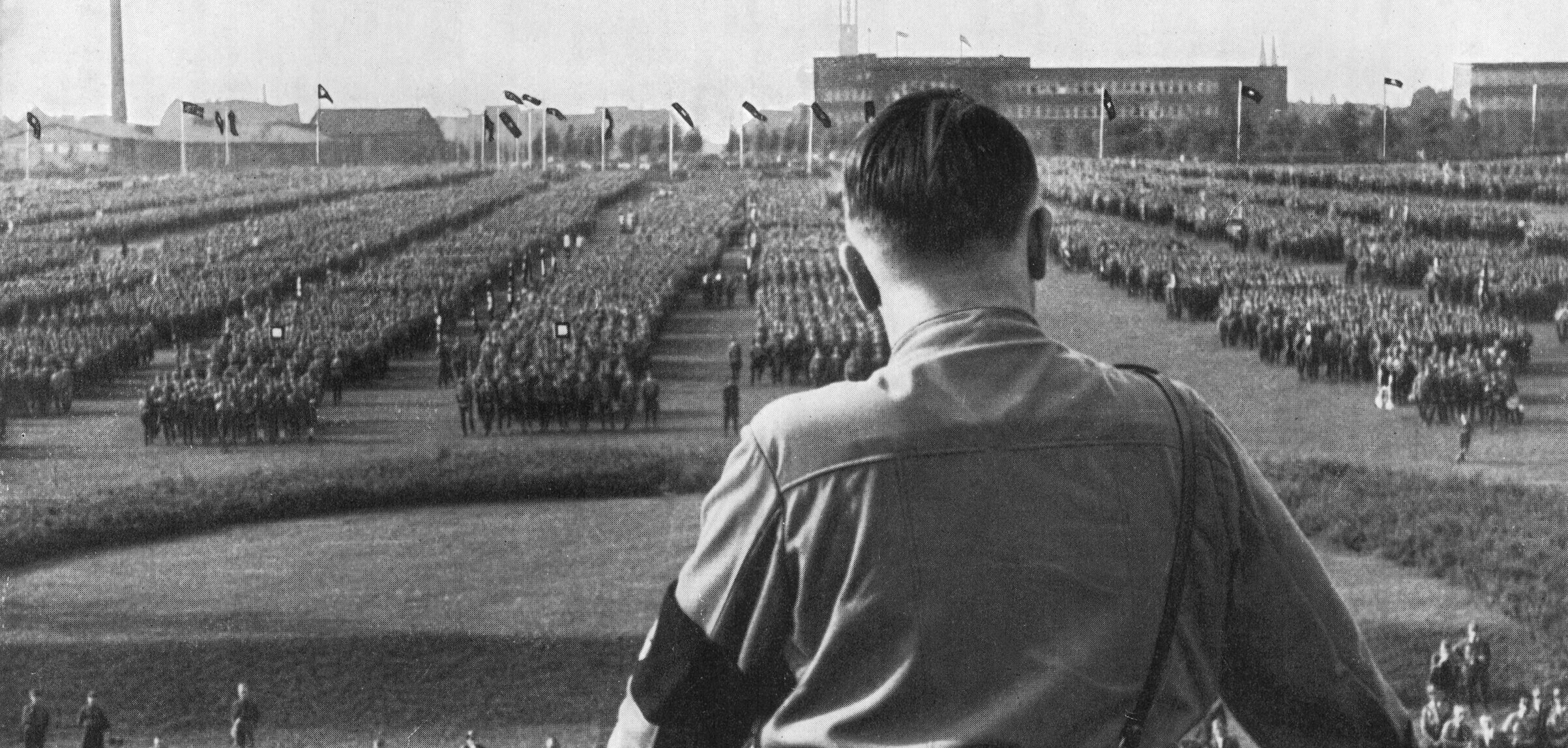

That’s the subject of the meme above, in which Remarque reacts to the horror in the expected, clichéd way, and Jünger decidedly does not.*** I think that’s also why so many people interpret Jünger so differently. War described this unflinchingly shouldn’t be exciting… should it? What do we make of someone who finds that he enjoys and excels at something so horrible? Hence the accusations of coldness or inhumanity, or, further, of jingoism or fascism or social Darwinism or worse.

Sympathy

But actually reading the book, one finds enjoyment of danger and conflict without bloodlust. Jünger describes killing plenty of enemy soldiers—often point-blank, intimately—but just as often he passes up the chance to kill an enemy. Interestingly, this happens more often in the later, wilder, more violent passages of the book from Operation Michael (Spring 1918) onward, and, in one episode late in the war, Jünger explicitly contrasts himself with a ferocious stormtroop leader he joins in an attack. Jünger, you might be surprised to learn by this point of the book, is invigorated by someone yet more eager than himself.

Similarly, Jünger takes no joy in destruction for its own sake. While never editorializing or effusively emoting over it, it is clear that the destruction of whole towns and villages and the annihilation of landscapes is a bad thing. And every time he encounters his enemies outside combat, he looks upon them with sympathy and even respect. Likewise with the French or Flemish civilians in the rear—he shows no disdain, no exploitative greed, no animosity whatsoever, and always interacts politely and even familiarly. Most often the civilians appear as friendly or affectionate figures, and Jünger presents their evacuation when the war reaches their homes as unfortunate. Again, without explicitly saying so.

Thrilling or horrifying? Ja.

All of which only brings us back, again and again, like Jünger himself, to the combat. And it is thrilling. Seldom have I read a true story with as much continuous excitement as when Jünger goes into the line with his company, endures British and French bombardment, gets stranded far ahead of the German lines and shoots his way out, is surprised by but manages to defeat a British Indian colonial unit far larger than his own, or, especially, when he begins the breathtaking, overwhelming assaults in the Spring 1918 offensive, with his men rushing over battlefields that have sat immovable for three years.

It is also horrible, with the destruction of lives by shrapnel, bullets, gas, infection, artillery—powerful enough simply to vaporize some men—and dumb accident all presented bluntly, in unstinting detail, like a naturalist describing lions taking apart a zebra. It could provoke what some on the internet call mood whiplash, but somehow Jünger conveys all of this to the reader as a sensible, coherent, unified experience.

One suspects that it really could not be thrilling without being horrible—and vice versa. This is a tension Jünger clearly felt and that Storm of Steel makes the reader feel like no other book, all of which is part of Jünger’s forthrightness. Most other war novels and memoirs skew toward the horrible; a few, mostly from long ago, toward the thrilling or exciting or even the morally uplifting.

Jünger refuses easier understandings of what he lived through. His work suggests that the people horrified by war are right. And so are the people thrilled by it. Throughout Storm of Steel, Jünger is describing a state, a condition, and how do you rage against a state? War just is.

Philosophizing

One gets all of this from reading between the lines, from letting the Storm pass over you, so to speak, and listening to the lightning and feeling the wind and the pelting rain. Jünger describes bluntly but doesn’t preach, at least not most of the time. There are isolated passages of reflection in which Jünger drifts into what Mark Twain—brutally but, to be frank, accurately—described as “the sort of luminous intellectual fog” of German philosophizing,† but he avoids the world-historical opining of Remarque or other explicitly antiwar authors.

One thinks of Dalton Trumbo’s novel Johnny Got His Gun, which begins as a brilliant modernist stream-of-conscious story and ends as a straightforward Marxist sermon, or the unfortunate Willy Peter Reese, who was killed on the Eastern Front during World War II and left behind an unfinished memoir so densely packed with philosophical and poetical musings as to be almost unreadable for long stretches.‡

The edition of Storm of Steel I read this time includes a short foreword by Karl Marlantes, veteran of Vietnam and author of the brilliant novel Matterhorn based on his experiences as a Marine platoon commander. Marlantes is the perfect person to introduce Jünger. Like Storm of Steel, Matterhorn is vividly and painstakingly descriptive and avoids overt philosophizing or didactic messaging, deriving its power from the forcefulness with which it presents what happened. Both have an absorbing, dreamlike quality once they take hold of the reader. In some places, both are a fever-dream.

Marlantes’s verdict on Jünger, with whom he feels an affinity despite also being separated by a vast gulf: he was “a different breed of man: the born warrior.”

Conclusion

Like I said, this is more a grab-bag of notes, observations, and meditations than a straightforward review. Like the war Jünger fought in and wrote about, Storm of Steel is fundamentally impossible to summarize and can only be described, and is therefore prone to misinterpretation. One has to experience it. And I strongly recommend experiencing Storm of Steel to everyone.

Notes:

*I do not own any German edition of the original, In Stahlgewittern, though that is on my wish list. This edition is the Michael Hofmann translation of Jünger’s last revision of the book in 1961. There is an online fan culture for the “original” 1929 English translation of Jünger’s second revision, though that translation is rife with inaccuracies and most widely available in a print-on-demand reprint that is apparently loaded with typos.

**The memoir that I think offers the closest point of comparison in tone and style to Storm of Steel—while still being a very different book—is EB Sledge’s With the Old Breed. Tellingly, both men became zoologists after the war.

***A further contrast between the two books that I’ll just drop here: Linguistically, their titles also suggest a key difference in tone and perspective. Remarque’s book, in German, is Im Westen nichts neues, i.e. “Nothing new in the West.” Im Westen is in the dative case, suggesting stasis and therefore pointlessness. Nichts neues, nothing new, is the book’s central, bitter irony. But Jünger’s title, In Stahlgewittern (a Gewitter is a thunderstorm), is in the accusative case, which in German suggests movement (one stands in a room datively, but goes in[to] the room accusatively). Grammatically, the title could just as accurately be translated Into the Steel Storm. This is precisely Jünger’s journey in the book, and where he takes the reader.

†To see more of Jünger in this mode, read Copse 125, a memoir in which he expanded upon one specific monthlong stretch in the trenches in the summer of 1918. The contrast is striking. I read it this past spring.

‡I read Reese’s book A Stranger to Myself a few years ago, also in a translation by Hofmann. Interestingly, where Hofmann includes as footnotes passages from Reese’s diaries—which, like Jünger, he had used as the raw material to construct a memoir—they are much more vivid, direct, and concrete than the memoir he based on them.