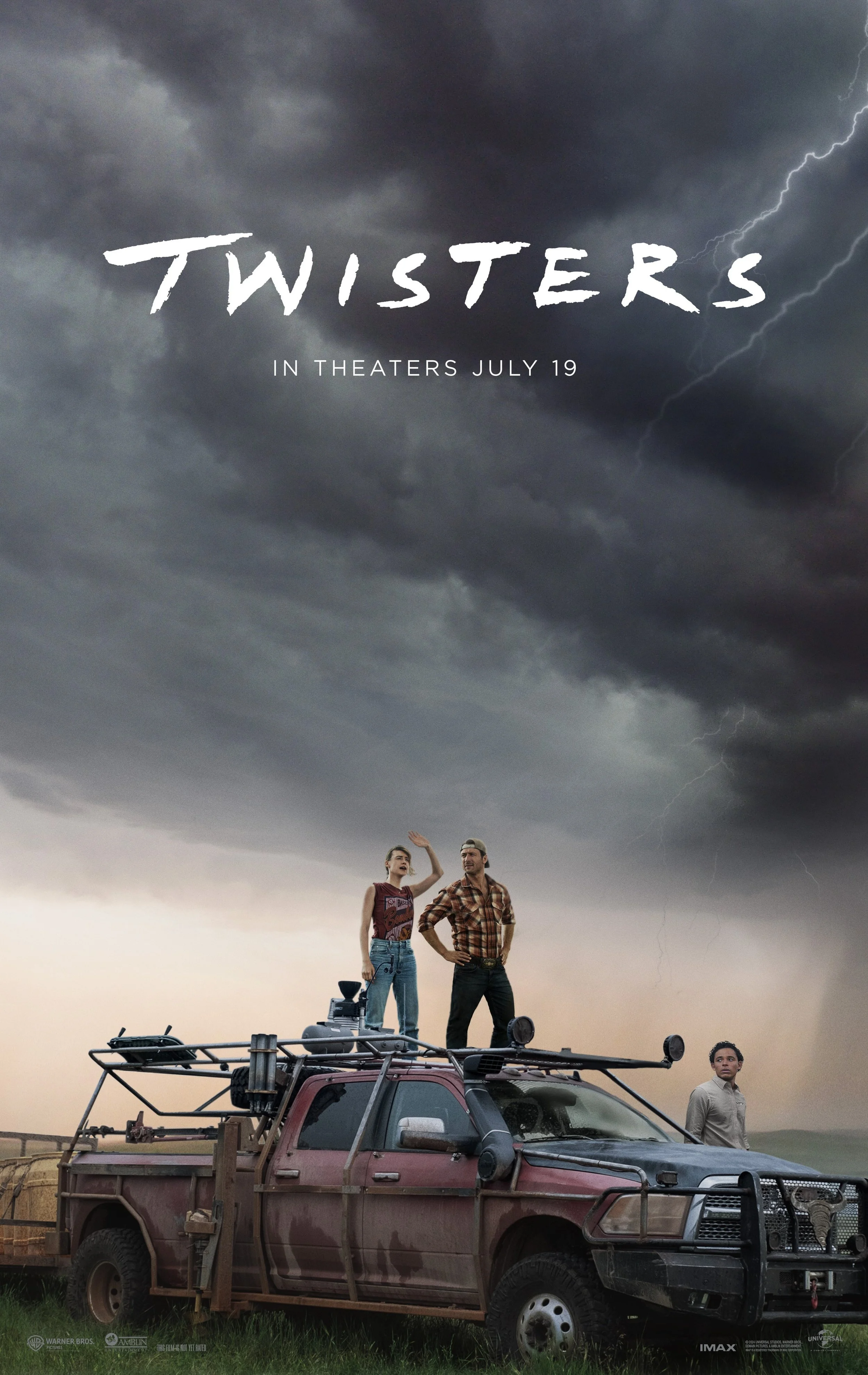

Twisters

/PhDs and Hillbillies—Glen Powell and Daisy Edgar-Jones unite to chase storms in Twisters

It’s been a slow year for movies in the Poss household, with Dune: Part Two and The Wild Robot being two of only three movies we’ve gotten really excited about. Over the weekend my wife and I finally got a chance to see the third, Twisters, after having to cancel plans to see it several times over the summer. We weren’t disappointed.

Twisters is old enough news now that I won’t recap the plot in any detail. Kate (Daisy Edgar-Jones) is a former meteorology PhD student who got several friends killed in an experiment. When Javi (Anthony Ramos), the only other survivor, approaches her about a new opportunity to learn more about tornadoes using new portable military radar, she agrees to a brief return to the field to look things over. With Javi and his corporately-sponsored team in Oklahoma, Kate meets Tyler Owens (Glenn Powell), a cocky amateur with a wildly popular YouTube channel. Then a monster storm arrives.

As a movie, Twisters is rock-solid old-fashioned entertainment, with good acting and a well-structured, suspenseful script that also makes room for much more realistic and nuanced characters than the original. Given the format in which we finally saw Twisters—projected on an inflatable outdoor screen with a portable sound system—I can’t fairly comment on a lot of the technical aspects of the movie. But despite the setting in which we saw it the movie looked and sounded great. I learned afterward that it was shot on 35mm film, which is a credit to the filmmakers. I hope to watch it again soon.

But while Twisters’ story and the technical aspects were good, they are not what made me want to write about it.

When the movie came out, our political schoolmarms were affronted that the movie did not lecture its audience on climate change. (The byline on that Salon piece sounded familiar, and, sure enough, that’s the same guy who wanted 1917 to sit the audience down for a talk on nationalism.) Again, to the filmmakers’ credit, the director explicitly stated in interviews that movies aren’t for “preaching”: “I just don’t feel like films are meant to be message-oriented.”

Hear hear. And yet, while Twisters does not “put forward a message” in the sense of “preaching,” like all well-crafted stories it does have something to say. And like all well-crafted stories, it does so not through speeches but through its characters.

This begins when Kate, tagging along with Javi’s well-funded storm-chasers, first meets the crowdfunded livestreaming Tyler. The two sides are explicitly set in opposition as “the PhDs” on Kate and Javi’s side and “hillbillies” on Tyler’s. Javi’s company receives funding in exchange for data, and Tyler receives YouTube money and adulation from his viewers in exchange for risking his life to chase storms. It’s a familiar American dynamic in microcosm—elites vs populists.

But while Twisters introduces these two sides in opposition, it doesn’t hold them there. Both sides have hidden depths. Beneath their slick equipment and university backgrounds, Kate and Javi genuinely care about using their research to help people, and beneath his media-hungry machismo, Tyler has actual scientific knowledge and wants to help, too. Neither is blameless—one takes money from a shady real estate mogul, the nearest thing the movie has to a villain, and the other hawks t-shirts. Despite all this, they are more alike than different, and both want to help people.

This last point is important, because the key moment in bringing Kate and Tyler together, working toward a common goal, is a small town rodeo, an event that opens with the national anthem and is presented completely unironically. There is no wink or condescension toward the people at the rodeo, and, significantly, it is here that Tyler first opens up to Kate and the two begin working together. Twisters is the first movie I can remember in a long time that unequivocally presents small-town American life as good and worth preserving, and the suspense of the film’s final act comes not only from whether Kate’s experiment will finally succeed, but whether Kate and Tyler can save a town in the path of a once-in-a-generation tornado. Why? Because the people there are worth saving, period, regardless of their political affiliation or whom they vote for.

Twisters does not preach, no, but it presents a vision of an America where the elites and the people, the PhDs and the hillbillies, work better together. That demands a common goal, and on one side realizing that the people are more than data or raw material, and on the other realizing that the elites are people, too, and being willing to work alongside them toward a common goal.

This may not be a life-changing movie or high art, but Twisters is well-crafted and both entertains and uplifts. That’s rare enough in this day and age, but Twisters also tells a story of what can united Americans, which is worth contemplating during an election year—or any year.