Ready to spew

/Trigger warning: This post contains untranslated French words and phrases. Appropriately, as you may be able to infer.

After some internationally public tableaux generated predictable—and, I think, entirely intentional—online outrage, I saw some equally predictable condemnations of the outraged for doing the thing all the kindhearted internet bien pensants love to condemn: “spewing hate.”

If a cliché is a “dead metaphor,” spewing hate must be the deadest of them all. But where most clichés are merely overused word pictures or verbal shortcuts, this one is also dangerous. J’accuse!

Spew is a very old word, almost unchanged in pronunciation from Old English spíwan and having retained both literal and figurative senses for its entire history. But what’s striking to me about spew is that as vomit or throw up or even puke have become far more commonly used for its literal meaning, its metaphorical use has been whittled down to almost the single expression spew hate. It’s rare now to see spew without hate tagging along behind it.

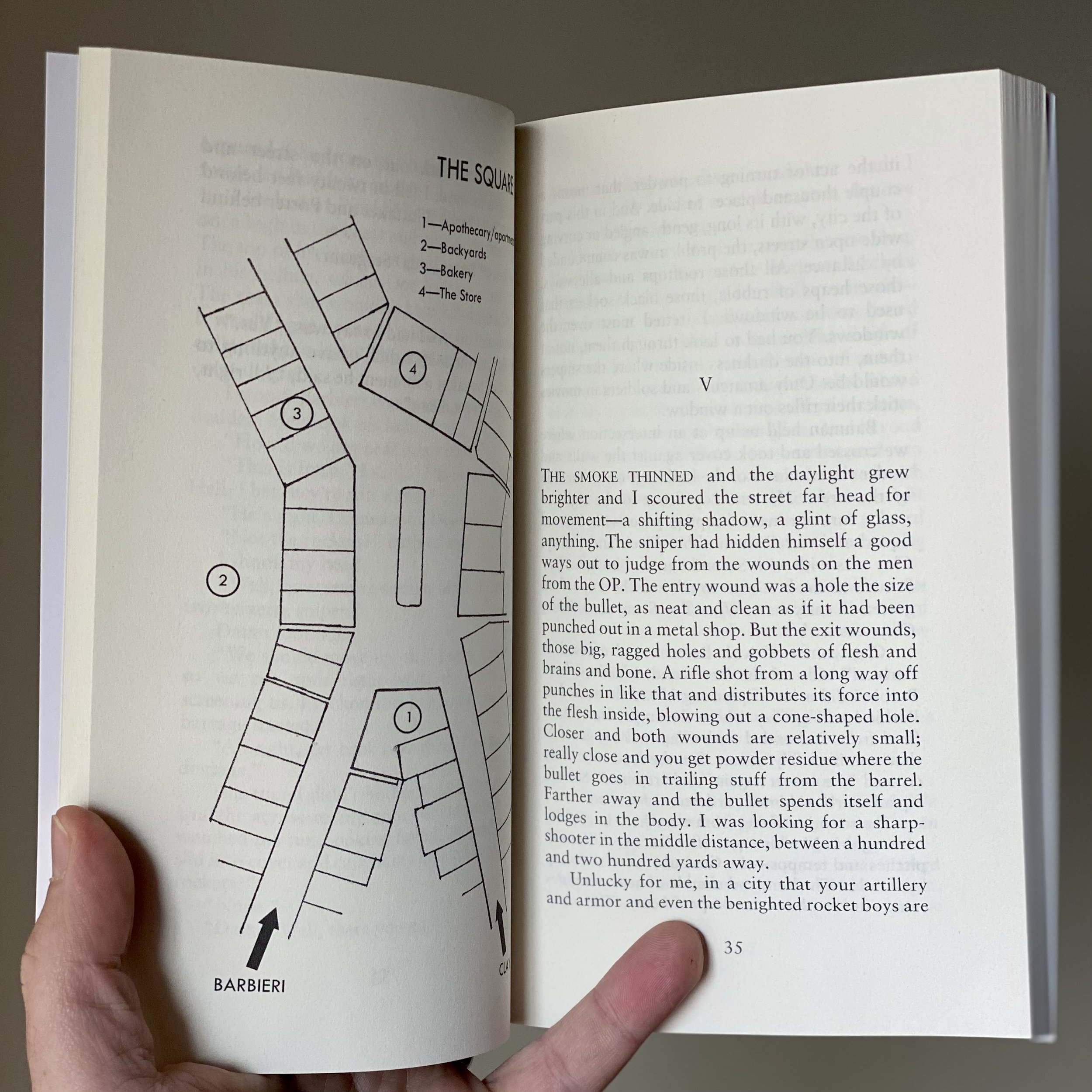

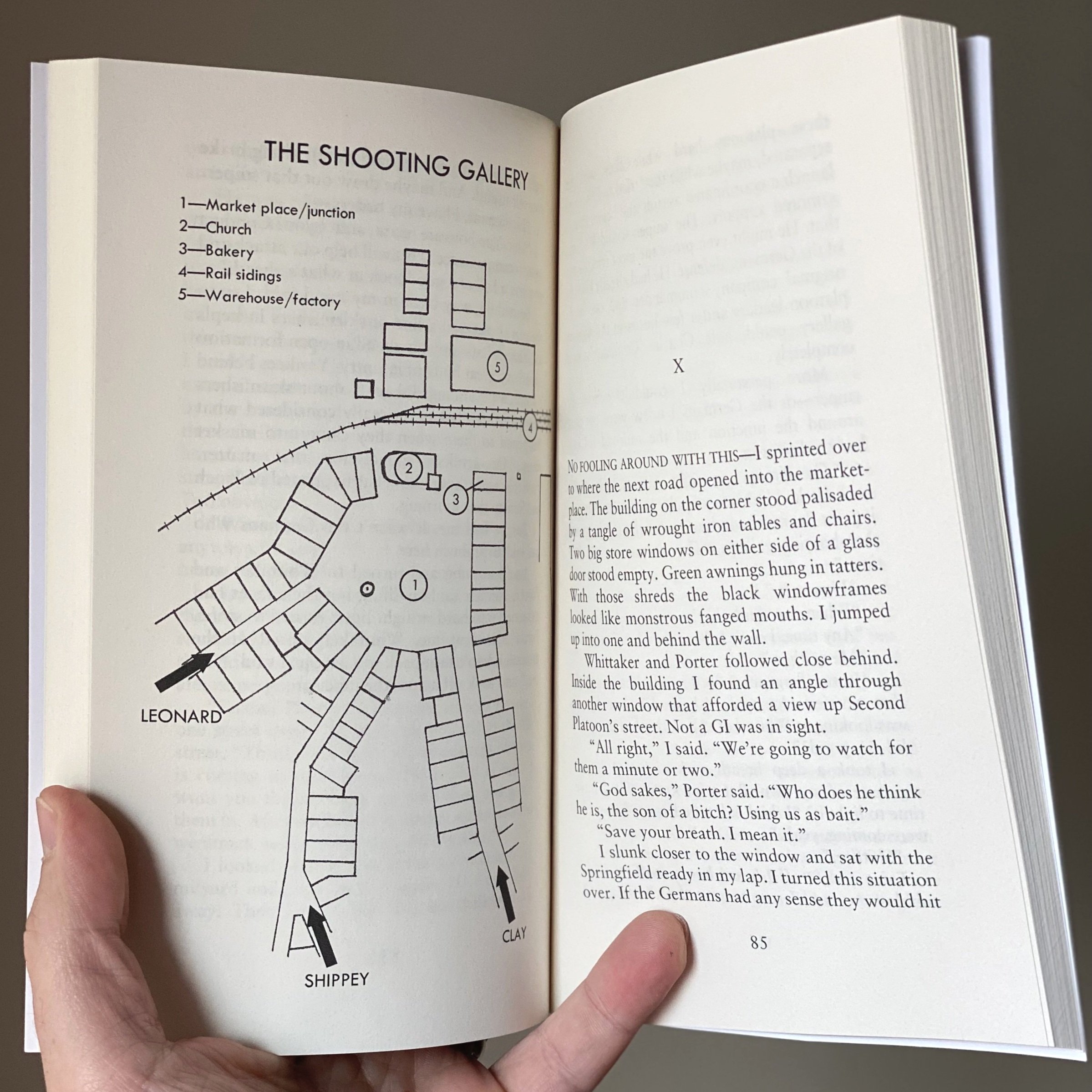

This is a relatively recent development. Here’s Google’s Ngram viewer for various versions of the phrase:

This particular combination of words originated in the 20th century but has taken off since 2000, especially in its most common form, spewing hate.

This jibes with my observations. I first noticed this phrase during college, when it became the de rigeur description of Mel Gibson’s drunken rant following his 2006 DUI arrest. (The unbroken climb in frequency for spewing hate in the chart above begins in 2005.) Given Gibson’s state of intoxication and what he had to say during his arrest, this was an almost accurate description.

But then I noticed that the phrase wouldn’t go away. To my increasing annoyance, within a few years the advocate of every bad opinion and every person caught saying something mildly rude on camera would inevitably be described as “spewing hate”—regardless of whether they could be described as “spewing” or whether what they had said was hateful. As Orwell and CS Lewis observed, words that get stuck within easy reach of popular use soon become yet more synonyms for something one either does or doesn’t like. They become clichés.

And this cliché isn’t just lazy, unimaginative, or gauche. Given the political and cultural valence it usually has, spewing hate also functions as a thought killer. This is where the metaphorical image does its nastiest work. Someone spewing hate is not communicating, they’re just vomiting, and what they have to say is vomit. It needs no consideration or engagement, just a mop and a man to hustle the sick person out the door.

This makes spewing hate a handy phrase for shutting down debate and preventing argument. And a cliché being a cliché, it is, of course, overused.

Its overuse makes it especially dangerous, for two reasons. First, it prevents legitimate argument. With regard to the events that prompted this post, lots of people have legitimate concerns and complaints, and describing them simply as “spewing hate” is an imperious culture war dismissal. Leave us, hateful paysan. Second—and more insidious—any openminded person who sees through this cliché, who investigates someone accused of “spewing hate” and finds them a reasonable person offering measured argument over legitimate concerns, will be more open to people who actually are in the hate business. It’s not only annoying and thought-killing, it’s self-defeating.

As always with clichés, avoid this one. Don’t use it. Don’t share material that does. Make yourself think about your words. And, in this case, just maybe, you’ll be able to consider someone else’s opinion, too.