Summer reading 2023

/This proved to be a pretty momentous summer. I published my fifth book and my wife and I welcomed twins, our fourth and fifth children, a few weeks ago, not long after I first announced it here. And somewhere in there were work, looking for more work, preparing for the babies’ arrival, a little bit of travel, and reading. I’m glad to say it was all good, the reading included. So here are my favorites from this busy but blessed summer.

For the purposes of this post, “summer” is defined as going from mid-May to last week, just before fall late-term courses began at my school. The books in each category are presented in no particular order and, as usual, audiobook “reads” are marked with an asterisk.

Favorite non-fiction

Looking back over the summer, I read a pretty good and unintentionally wide-ranging selection of non-fiction—history, biography, memoir, literary criticism, and, most surprising for me, self-help! Here are the best in no particular order:

The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front, 1915-1919, by Mark Thompson—A well-written and comprehensive history of the Italian Front in the First World War, a front fought over unforgivingly rugged mountain terrain. Thompson focuses primarily but not exclusively on Italy: its history from the Risorgimento to 1914, the role of nationalism and irredentism in its rush toward an unpopular war of aggression against Austria-Hungary, its appalling mismanagement of the war, and the effects of the war on its politics, military, culture, literature, and, most painfully, its people. Though little-known or understood in the English-speaking world today—outside of high school lit classes forcing A Farewell to Arms down a new generation of unreceptive throats—the Italian Front was a continuous shambles, with proportionally higher casualties per mile than even the Western Front. Thompson gives less detailed coverage to the Austrian side, which is what I was actually most interested in when I picked up this book, but the book is so solidly researched and well-presented that this is not a flaw. Highly recommended if you want to round out your understanding of the war in Europe.

Cheaper by the Dozen, by Frank B Gilbreth and Ernestine Gilbreth Carey—A charming, funny, and genuinely sweet memoir of a unique family and its colorful, larger-than-life father. I read this to my wife a chapter at a time before bed and we both loved it.

The Habsburg Way: Seven Rules for Turbulent Times, by Eduard Habsburg, Archduke of Austria—A short introduction to a great old family, its history, its faith, and its methods. Far from a relic of a bygone, outdated world of monarchs and arranged marriages, the Habsburgs still have things to teach us, especially as the world since the demise of Austria-Hungary has so spectacularly lost its way. The “rules” in this volume range from the dynastic and political to the individua and spiritual: marriage and childrearing, the principle of subsidiarity, living a life of devout faith, courage, dying a worthy death. Habsburg writes with warmth and humor, using his family’s rich past as a mine of stories supporting his points, making this one of the best surprises of my summer.

Poe for Your Problems: Uncommon Advice from History’s Least-Likely Self-Help Guru, by Catherine Baab-Muguira—This book’s thesis might have been Chesterton’s line that “anything worth doing is worth doing badly.” That a figure like Edgar Allan Poe—born into and marked by tragedy all his days, with a doomed love life and bottomless wells of both self-promotion and self-sabotage—could still be the object of admiration over 170 years after his death is a sign that he did something right. Baab-Muguira, in a series of wry how-to chapters, lays out both Poe’s tragicomic life story and how he succeeded despite his failures. I had hoped to write a full, more detailed review of this wonderful and fun little book—and maybe I’ll have the time sometime soon to do so—but please take this short summary as a strong recommendation.

Crassus: The First Tycoon, by Paul Stothard—A good short biography of an important but elusive figure from the end of the Roman Republic. Considering the role Crassus played in the careers of Pompey, Caesar, Cicero, and even Catiline, it is striking that his life does not have the extensive coverage accorded to any of those other men. Stothard gathers what information we have about Crassus and interprets it judiciously, leaving plenty of space open for the unknowable, and concludes with a good detailed history of Crassus’s fatal campaign into Parthia.

The Battle for Normandy 1944, by James Holland—The ninth entry in the beautifully illustrated Ladybird Expert series on the Second World War, this little book covers everything from the Allies’ preparations to breach Fortress Europe through D-Day and the bloody battles in the intractable Norman countryside that followed to the breakout in late summer. It reads like a fast, sharp precis of Normandy ‘44, Holland’s much longer history of the campaign. This is a great little series and Holland has done a good job of summarizing such vast and complicated events. I look forward to the three remaining volumes.

The Battle of Maldon: Together with The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth, by JRR Tolkien, Peter Grybauskas, Ed.—A wonderful new addition to my Tolkien shelf, this volume collects a miscellany of texts related to the fragmentary Anglo-Saxon epic The Battle of Maldon, which relates a tragic defeat at the hands of the Vikings in 991. Included are Tolkien’s own translation of Maldon, a selection of his notes on the poem, relevant excerpts from a number of his critical essays, and “The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm’s Son,” a verse composition for two voices designed as a sequel to Maldon. Whether you love Tolkien, Anglo-Saxon history and poetry, or all three, this is a welcome treasure trove. I blogged two excerpts here: one about the transmission of poetry or any other tradition across generations, and one about those times—more common than skeptics care to admit—when the literary and the real coincide.

No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men, by Anthony Esolen*—Part paean, part elegy, part polemic. Esolen forcefully argues that saving masculinity—and, inextricably, femininity—from gender ideology is not only desirable or correct but a necessity. I think I agree with everything Esolen sets out, but I kept wishing for more effort toward persuasion for the many who will be hostile to his message. Then again, simply reaffirming the obvious and reinforcing those struggling to live out the truth is a difficult enough task now, and quite necessary and welcome on its own.

Favorite fiction

My summer was pretty light on good fiction—with the exception of John Buchan June, which I summarize in its own section below—but here are five highlights in no particular order:

Journey to the Center of the Earth, by Jules Verne, trans. Frank Wynne—A fun diversion, and the first Verne I’ve read since childhood. And it also prominently features Iceland! This is a convincing and involving if not remotely plausible adventure, and the effort Verne puts into situating the story within the cutting-edge scientific knowledge of his day made me realize his place in Michael Crichton’s DNA. I began by reading a reprint of the original English translation but switched to the new translation available from Penguin Classics, which is more accurate and apparently restores a lot of material cut from or modified by the original translators.

The Napoleon of Notting Hill, by GK Chesterton—An early Chesterton novel I’ve been meaning to read for years. Worth the wait. Taking place in a near-future London in which very little has actually changed, the one major difference is that the monarchy has become a randomly elected lifetime position. When the eccentric and flippant Auberon Quin is elected and decides to refortify the neighborhoods of London, prescribe feudal titles and heraldic liveries for their leaders, and insist on elaborate court etiquette—all purely ironically, as a lark—he doesn’t count on one young man, Adam Wayne, becoming a true believer in this refounded medieval order. All attempts to crush Wayne end in cataclysmic street violence, and the novel concludes with a genuinely moving twilight dialogue on the field of the slain. This is Chesterton at his early energetic best, with some of the verve and freshness of The Man Who was Thursday about it. I reflected on a short passage from the beginning of the novel here.

The Twilight World, by Werner Herzog, trans. Michael Hofmann—A hypnotically involving short novel about Hiroo Onoda, a Japanese officer who carried on a guerrilla campaign in the Philippines from 1945 to 1974—decades after the end of World War II. Herzog evokes the isolation and paranoia of Onoda and his handful of comrades, who always manage to find a reason to believe the war has not ended, as well as the passage of time. An epic story briskly and powerfully told. Full review on the blog here.

The Night the Bear Ate Goombaw* and Real Ponies Don’t Go Oink,* by Patrick F McManus—Two collections of hilarious articles and tall tales from the late outdoor writer Patrick McManus. His stock of humorous characters like cantankerous old time outdoorsman Rancid Crabtree or childhood buddy Crazy Eddie Muldoon is especially rich, and all of his stories are written with a wry, self-deprecating irony that makes them doubly enjoyable. The title story in The Night the Bear Ate Goombaw is still one of the funniest things I’ve ever read. My wife and I listened to the excellent audiobook versions performed by Norman Dietz during 1:00 and 4:00 AM feedings for the twins.

John Buchan June

For the second annual John Buchan June I didn’t manage to make it through as many of Buchan’s novels as last year, reading only seven, but they were a solid assortment from the middle of his career and included serious historical fiction, espionage shockers, a wartime thriller, a borderline science fiction tale, and the first of the hobbit-like adventures of retired grocer Dickson McCunn.

The seven I read, in order of posting about them, are below. My full John Buchan June reviews are linked from each title.

Witch Wood (1927)

Huntingtower (1922)

The Dancing Floor (1926)

Mr Standfast (1918)

The Blanket of the Dark (1931)

The Gap in the Curtain (1932)

The Three Hostages (1924)

Of these, I think my favorite was certainly Witch Wood, a seriously spooky historical folk horror novel set in 17th-century Scotland. The two Sir Edward Leithen adventures The Dancing Floor and The Gap in the Curtain, with their own hints of the supernatural or uncanny, as well as the first Dickson McCunn novel, Huntingtower, were strong contenders as well, but Witch Wood also has great depth and therefore that much more power. I hope to reread it sometime soon.

Kids’ books

A Picture Book of Davy Crockett, by David Adler, illustrated by John and Alexandra Wallner—A short kids’ biography of Crockett with fun storybook illustrations that manages to give a surprisingly detailed and nuanced version of his life story and historical context. I was pleasantly surprised by this book and intend to seek out more in Adler’s series of picture book biographies.

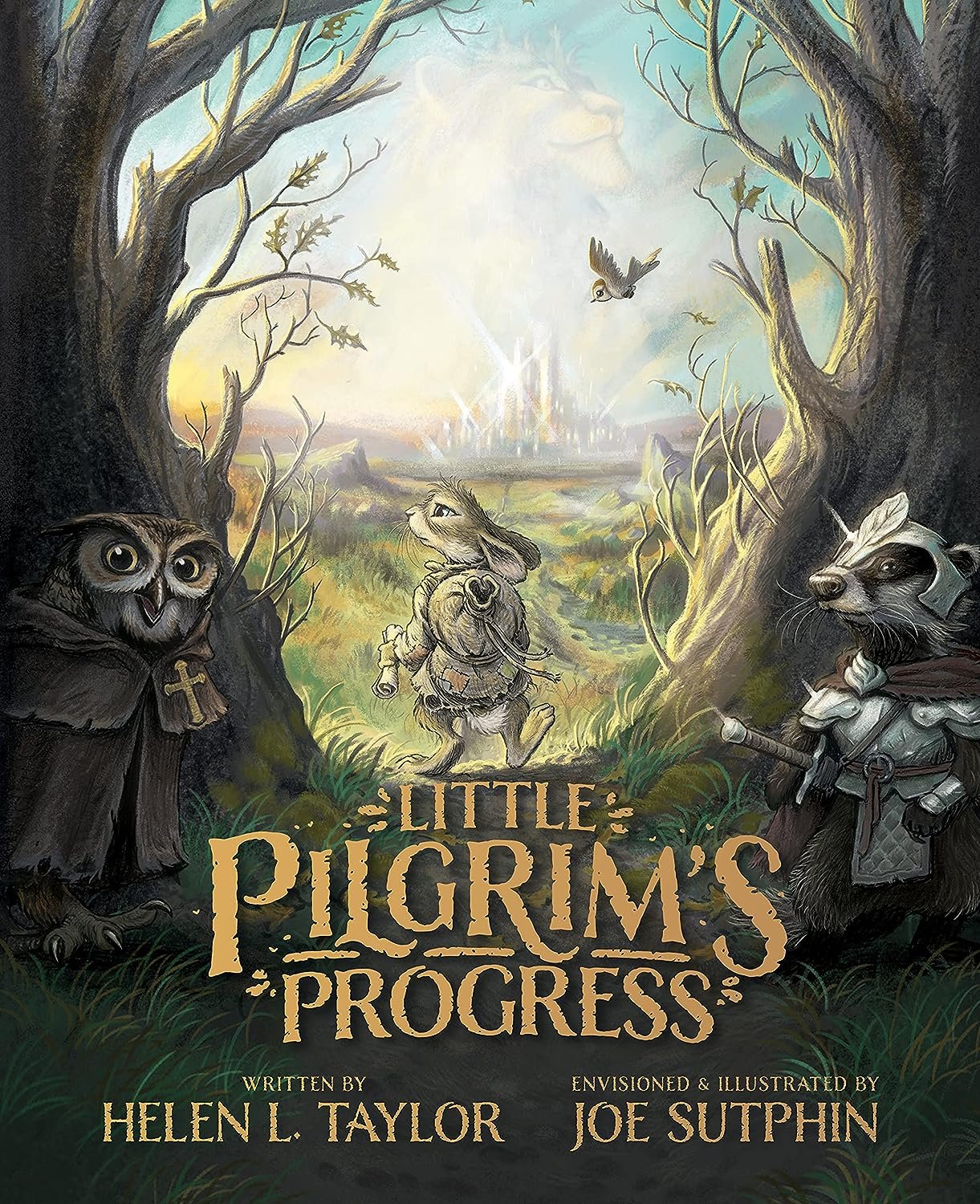

The Little Pilgrim’s Progress, adapted by Helen L Taylor, illustrated by Joe Sutphin—An adaptation of John Bunyan’s classic for children, with simplified language, a streamlined plot, and anthropomorphic animals instead of people, this still powerfully evokes the richness and pathos of the original. I wept at least twice while reading it out loud to my kids, who loved the whole thing and still talk about the characters. Sutphin’s illustrations are also beautiful and kid-friendly. I very much look forward to his graphic novel adaptation of Watership Down, which comes out this fall.

The Phantom of the Colosseum, by Sophie de Mullenheim, trans. Janet Chevrier—The first volume of the In the Shadows of Rome series, this is a fast-paced, suspenseful story set during the reign of Diocletian. Three Roman boys—Titus, Maximus, and Aghiles, Maximus’s Numidian slave—break into the Colosseum in search of a thief and find themselves involved in the efforts of Christians to survive persecution. Though none of the main characters converts—a rarity in a Christian novel—they find their assumptions about the believers challenged and their consciences pricked. My kids greatly enjoyed this adventure and we’re now reading the sequel, A Lion for the Emperor.

The Go-and-Tell Storybook, by Laura Richie, illustrated by Ian Dale—The third in a series of beautifully illustrated picture books by Richie and Dale, this one covers a large part of the Book of Acts and tells the stories of the first apostles and the spread of the Church beyond Judaea all the way to Athens and Rome. It’s rare to get such detailed coverage of this material in a children’s book, which I greatly appreciated, and it afforded many opportunities to talk about history and the Church with our kids.

Looking ahead

You won’t be surprised to learn that my reading has slowed down a bit over the last month or so, but I’m glad to say I’m still enjoying plenty of good stuff. In addition to the historical kids’ adventure novel set in Rome I mentioned above, right now I’m working on a supernatural espionage thriller by Tim Powers and War Horse, by Michael Morpurgo, which my daughter thoughtfully brought me from her classroom library. There’s more, and there’s always the to-read list. You’ll hear about the best of it after this semester ends, a respite I already look forward to.

Until then, I hope y’all will check some of these out and that whatever you find, you’ll enjoy. Thanks for reading!