Willy Wonka’s hidden Nazi joke

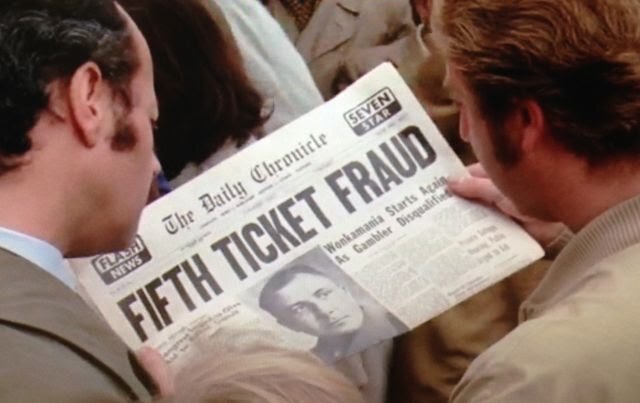

/Anyone who watched Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory as a kid remembers the movie’s immense weirdness, the streaks of darkness that run through it like a layer of fudge in cake, and the crushing disappointment of Charlie Bucket when the last golden ticket has been found. According to the news report in the film, “a gambler in Paraguay” found the ticket, ending the contest. The news anchor holds up a picture of the lucky winner, an old-fashioned studio portrait of a doughy but well-dressed man.

Only later, after Charlie’s spirits have begun to rebound and he has bought Grandpa Joe a Wonka bar, do we learn that the last ticket was a forgery and the contest is still on.

“Can you imagine the nerve of that guy?” a man looking at the headline reporting the fraud says. “Trying to fool the whole world?”

There’s a joke lost in the shuffle here, one that was certainly lost on me as a kid wondering why the first four winners were children whom we met and learned a little about while the fifth was a middle-aged man in a photo: our shady South American gambler is Martin Bormann.

The 1934 portrait of Martin Bormann used by Willy Wonka’s filmmakers. The Reichsleiter rank insignia on his collar was airbrushed out for the film.

As Adolf Hitler’s personal secretary and Chief of the Nazi Party Chancellery, Martin Bormann was not only one of Hitler’s closest staff members and advisers but the second most powerful man in the Nazi Party. He was a longtime Party member and—following an act of political violence as an accomplice of Rudolf Höss, the man who would go on to command Auschwitz—a convicted murderer, and he ruthlessly used his positions to accrue and hang onto immense power. By the end of the war, because of his amoral hunger for power, his utter lack of scruples, and his tight control over access to Hitler himself, he had become one of the most feared and hated men in Germany. Party insiders called him “der braune Schatten”—The Brown Shadow or Brown Eminence because of his closeness to the Führer.

After Hitler killed himself on April 30, 1945, the survivors of the Führerbunker banded into small groups to try to break out of Berlin, which had been surrounded and overrun by the Soviet Red Army in the previous weeks. Bormann joined one of these groups and, after leaving the bunker and the ruins of Hitler’s headquarters, took cover behind a Tiger tank that was fighting its way up a rubble-jammed street. The Tiger took Russian fire and Bormann was thrown from his feet, but others ran into him again later on. The last person confirmed to have seen Bormann in Berlin was Artur Axmann, head of the Hitler Youth, who spotted Borman and Ludwig Stumpfegger—a Nazi doctor who had helped Joseph and Magda Goebbels poison their six children—lying on their backs near a railroad station.

After that, as far as Allied investigators were concerned, Bormann disappeared.

As one of the leading Nazis in the Third Reich, Bormann was at the top of the Allies’ most wanted lists. The Allies viewed him as so important to the functioning and the crimes of the Reich that he was tried in absentia at Nuremberg alongside Nazi leaders like Hermann Göring, Albert Speer, Rudolf Hess, Wilhelm Keitel, and Joachim von Ribbentrop—men who had actually been caught. The Nuremberg court convicted Bormann of war crimes and sentenced him to hang.

But they never caught him. As historian Luke Daly-Groves documents in Hitler’s Death, American and British intelligence services received a flood of tips and reported sightings for years—Brazil, Switzerland, Denmark, Egypt, England, the United States, Spain. He was reported to be living disguised as a monk in Rome (or maybe Spain) or to have fled via U-boat (or maybe helicopter) to Argentina (or maybe a Tibetan monastery) with Hitler. British intelligence received so many contradictory leads that Bormann’s supposed travel itinerary became the subject of jokes. And because of the conflicted but not mutually exclusive eyewitness accounts of survivors and the total lack of legitimate leads following the war, these agencies were confident that Bormann was dead. But the rumors continued, aided by a sensationalist media, and eventually, probably because so many Nazis who had escaped had fled to South America, the rumored location of Bormann’s refuge settled there.

And that’s the joke. The elusive man in South America faking the golden ticket is a wanted Nazi war criminal.

In his making-of book Pure Imagination, Mel Stuart, Willy Wonka’s director, acknowledges the joke, and that it didn’t land. “The scene was never as successful as I had hoped.” He also thinks he knows why: “twenty-five years after World War II, very few people knew or cared who Bormann was.”

Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory came out in 1971. In December of 1972, Martin Bormann was found. Construction workers near the Berlin railway station where Axmann had last seen Bormann uncovered two sets of human remains. One was the loathsome Dr. Stumpfegger. Dental analysis and, in the 1990s, DNA comparison with an elderly cousin, confirmed the other body’s identity—it was Martin Bormann. Glass fragments in the skull’s teeth showed that Bormann, like his Führer, had killed himself, but with cyanide rather than a bullet.

That fifth golden ticket proved even phonier than we thought.