What's wrong, Chesterton?

/February, a whole month of recurrent sickness—for me and my kids—heavy work projects, and terrible weather, has also accidentally turned into GK Chesterton month on my blog. I’ve posted on his attitude toward argument and controversy and the lack of any real controversy in his world—and ours—and I also looked at his enviable ability to laugh at himself. I’ll end the month with a tiny bit of Chesterton detective work.

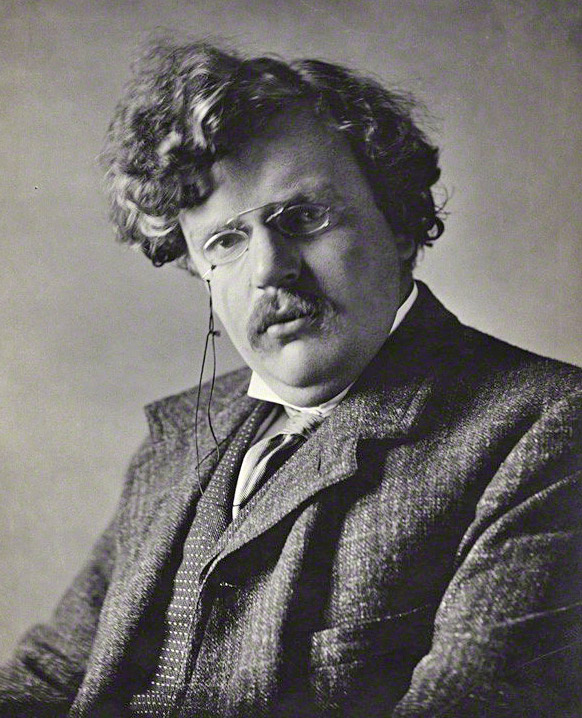

G.K. Chesterton c. 1909

Yesterday, a colleague pointed me toward this post on the most frequently misquoted Christian writers. Chesterton was on there for a number of quotes, misquotes, and apocryphal sayings, perhaps the most famous of which was this:

In answer to a newspaper’s question, “What is Wrong With the World?” G. K. Chesterton wrote in with a simple answer: “Dear Sirs, I am.”

I’ve seen a couple different versions of this story with slight variations—sometimes Chesterton’s answer comes in response to a survey of journalists or something similar, sometimes it’s slightly wordier—but the gist is always the same, and it’s easy to see why it sticks around. It’s been quoted by present day evangelical writers as prominent as Tim Keller. It’s cheeky and succinct, worthy of a man who enjoyed his bon mots as much as his beer. But also not quite true.

If you want to confirm a quotation’s authenticity—and you should—it’s relatively easy, and this was easy to disprove, as there are plenty of places logging it as doubtful or inauthentic. Wikiquote includes it in its “misattributed” section on Chesterton’s page. The American Chesterton Society had a rather noncommittal post on the quotation a few years ago, as did a Chesterton enthusiast’s blog.

But as it happens, the latter blog post included a couple of important tidbits. First, it clarified the actual, correct wording of Chesterton’s reply:

In one sense, and that the eternal sense, the thing is plain. The answer to the question, “What is Wrong?” is, or should be, “I am wrong.” Until a man can give that answer his idealism is only a hobby.

This, helpfully, provides a lot more context and explanation about what exactly Chesterton meant. It’s also a handy passage to plug into Google. But alas, nothing.

Second, the blogger’s post indicated that Chesterton’s letter came in response to another letter not from the Times, but from the Daily News—a newspaper founded by Charles Dickens, one of Chesterton’s literary heroes—and from a specific issue: August 16, 1905. I don’t know where the blogger dug this info up, but it was enough to go on. It turned out to be correct.

Having turned up nothing via Google, and beginning to suspect that this was either elaborately fabricated or a previously totally unavailable Chesterton essay, I searched for the Daily News itself. The paper merged with another in the 1910s and no longer exists, but a free trial of the British Newspaper Archive allowed me to look at digital scans of its entire archives and the specific issue of the paper noted in the blogger’s post.

And behold:

The Daily News, August 16, 1905

Chesterton’s complete letter to the editor in response to “A Heretic,” and the germ of the oft-repeated misquotation, right there.

As I mentioned, I was flummoxed that this bit of Chesterton lore was unavailable anywhere online, especially since the misquoted version has proved so persistent and vexing. So I’ve transcribed the entire text of the letter and included it below so that the whole thing is available somewhere. I hope having the full text available will prove a good resource for anyone, like me, hunting for the source of that famous story. I’ve included a handful of hyperlinks to things that might clarify some of Chesterton’s allusions or asides.

Like all of Chesterton’s work, it’s amusing and thought-provoking. And despite coming early in his career—three years before his novel The Man Who Was Thursday, five before the book What’s Wrong with the World—and from a lost world—nine years before the First World War!—in many ways as alien to us now as the antebellum South, medieval Britain, or republican Rome, much of his concern is eerily prescient, particularly in an age of religious flabbiness, unease with the status quo, political strife, the squandering of inherited blessings, and increasingly insistent reliance on the State.

This was by no means a difficult bit of detective work—I’m no Father Brown—but I enjoyed the hunt, and I enjoyed reading a new bit of recovered GKC. I hope y’all enjoy and benefit from it as well.

* * * * *

From the Daily News, August 16, 1905

Sir,—I must warmly protest against people mistaking the uneasiness of “A Heretic” for a sort of pessimism. If he were a pessimist he would be sitting in an armchair with a cigar. It is only we optimists who can be angry.

“Political or economic reform will not make us good and happy, but until this odd period nobody ever expected that they would.”

One thing, of course, must be said to clear the ground. Political or economic reform will not make us good and happy, but until this odd period nobody ever expected that they would. Now, I know there is a feeling that Government can do anything. But if Government could do anything, nothing would exist except Government. Men have found the need of other forces. Religion, for instance, existed in order to do what law cannot do—to track crime to its primary sin, and the man to his back bedroom. The Church endeavoured to institute a machinery of pardon; the State has only a machinery of punishment. The State can only free society from the criminal; the Church sought to free the criminal from the crime. Abolish religion if you like. Throw everything on secular government if you like. But do not be surprised if a machinery that was never meant to do anything but secure external decency and order fails to secure internal honesty and peace. If you have some philosophic objection to brooms and brushes, throw them away. But do not be surprised if the use of the County Council water-cart is an awkward way of dusting the drawing-room.

In one sense, and that the eternal sense, the thing is plain. The answer to the question “What is Wrong?” is, or should be, “I am wrong.” Until a man can give that answer his idealism is only a hobby. But this original sin belongs to all ages, and is the business of religion. Is there something, as “Heretic” suggests, which belongs to this age specially, and is the business of reform? It is a dark matter, but I will make a suggestion.

Every religion, every philosophy as fierce and popular as a religion, can be regarded either as a thing that binds or a thing that loosens. A convert to Islam (say) can regard himself as one who must no longer drink wine; or he can regard himself as one who need no longer sacrifice to expensive idols. A man passing from the early Hebrew atmosphere to the Christian would find himself suddenly free to marry a foreign wife, but also suddenly and startlingly restricted in the number of foreign wives. It is self-evident, that is, that there is no deliverance which does not bring new duties. It is, I suppose, also pretty evident that a religion which boasted only of its liberties would go to pieces. Christianity, for instance, would hardly have eclipsed Judaism if Christians had only sat in the middle of the road ostentatiously eating pork.

Yet this is exactly what we are all doing now. The last great challenge and inspiration of our Europe was the great democratic movement, the Revolution. Everything popular and modern, from the American President to the gymnasium in Battersea Park, comes out of that. And this Democratic creed, like all others, had its two sides, the emancipation and the new bonds. Men were freed from the dogma of the divine right of Kings, but tied to the new dogma of the divine right of the community. The citizen was not bound to give titles to others, but was bound to refuse titles for himself. The new creed had its saints, like Washington and Hoche; it had its martyrs, it had even its asceticism.

Now to me, the devastating weakness of our time, the sin of the 19th century, was primarily this: That we chose to interpret the Revolution as a mere emancipation. Instead of taking the Revolution as meaning that democracy is the true doctrine, we have taken it as meaning that any doctrine is the true doctrine. Instead of the right-mindedness of the Republican stoics, we have the “broad-mindedness” of Liberal Imperialists. We have taken Liberty, because it is fun; we have left Equality and Fraternity, because they are duties and a nuisance. We have Liberty to be unequal. We have Liberty to be unfraternal. At the last we have Liberty to admire slavery. For this was the just and natural end of our mere “free-thinking”—the Tory Revival. Liberalism was supposed to mean liberty to believe in anything; it soon meant liberty to believe in Toryism. Democracy in losing the austerity of youth and its dogmas has lost all; it tends to be a mere debauch of mental self-indulgence, since by a corrupt and loathsome change, Liberalism has become liberality.—Yours, etc.,

G. K. Chesterton