Hacksaw Ridge

/Andrew Garfield as Desmond Doss in Hacksaw Ridge

After a break for Easter and another week's hiatus due to illness, Historical Movie Monday returns with a film about a peaceful man in a time of war, a man of principle in a time of expedience, a man of transcendent faith in a world narrowed to naked survival. The film is Hacksaw Ridge, starring Andrew Garfield.

“With the world so set on tearing itself apart, it don’t seem like such a bad thing to me to want to put a little bit of it back together.”

The history

The US Marine Corps and Army landed on Okinawa on April 1, 1945. It was Easter Sunday—and April Fool's Day. Eugene Sledge, a Marine mortarman, later remembered how

When our wave was about fifty yards from the beach, I saw two enemy mortar shells explode a considerable distance to our left. They spewed up small geysers of water but caused no damage to the amtracs in that area. That was the only enemy fire I saw during the landing on Okinawa. It made the April Fool's Day aspect even more sinister, because all those thousands of first-rate Japanese troops on that island had to be somewhere spoiling for a fight.

The Maeda Escarpment is visible running northwest to southeast across the top of this map, north of Shuri. Each topographical relief line represents ten meters of elevation.

Okinawa, the largest of the Ryukyu chain, was about 70 miles long and lay about 400 miles south of the main Japanese archipelago. Its size and proximity meant that, once captured from its defenders, the island would be a close airbase for the firebombing of Japanese cities, and, in the long term, a critical staging area for the long-awaited invasion of Japan.

Fortunately, that invasion would never come. Unfortunately, it was, at least in part, because of the 82 days of grueling combat that followed the landings. The Japanese fought from dense networks of mutually-supporting bunkers, pillboxes, and tunnels that slowed the American advance in the southern half of the island to a crawl. Okinawa's rugged landscape and torrential spring rains added to the misery. American and Japanese corpses rotted half-buried in craters. According to Sledge, Okinawa "was choked with the putrefaction of death, decay, and destruction."

The center of Japanese resistance in the southern half of Okinawa was the town of Shuri. The Japanese commanders were headquartered in the town's medieval fortress, Shuri Castle, and the town formed the nucleus of a series of heavily fortified defensive rings, carefully constructed to take maximum advantage of the terrain. What 20,000 Japanese defenders had done at Iwo Jima, which the Marines had taken at the cost of almost 7,000 lives, the 100,000 defenders of Okinawa would far surpass. By the end of the battle, over 12,000 Americans had been killed in action, thousands of others had died of wounds, and another 50,000 had been wounded. The vast majority of the island's 100,000 Japanese defenders were killed, and around 150,000 Okinawan civilians, caught in the storm, died too.

Among the toughest strongpoints of Shuri's defenses was the Maeda Escarpment, a flat-topped ridge with a sheer cliff face running diagonally across the island for several thousand yards. The ridge was honeycombed with tunnels and interconnected bunkers. According to a unit history of the 77th, after a tank fired white phosphorous into one bunker, "within fifteen minutes observers saw smoke emerging from more than thirty other hidden openings along the slope." Here, at the end of April and beginning of May, elements of the 77th Infantry Division repeatedly scaled and assaulted Japanese positions, only to be repulsed with heavy casualties. Previous assaults by another unit had resulted in 1,000 casualties in four days.

Desmond Doss receives the Medal of Honor from President Harry Truman

Here, over the course of several days at the beginning of May, Private Desmond T. Doss of Lynchburg, Virginia, a combat medic in the 77th, repeatedly entered the combat zone to rescue wounded men—sometimes isolated from the main body of his unit by 200 yards or lying within 30 feet of enemy positions—and even stayed on the ridge giving first aid after his unit fell back. A lanky, rail-thin young man, Doss would drag or carry his wounded comrades to cover, administer first aid, and carry them to the edge of the cliff where he would lower them by rope for evacuation to field hospitals. He continued to rescue and treat the wounded after the capture of the Escarpment—by now nicknamed Hacksaw Ridge—and their advance on Shuri until he was himself wounded and evacuated on May 21.

Doss later estimated he had saved around 50 men over the course of those days; his commanders estimated 100. The army settled on 75. For his actions there and throughout the Battle of Okinawa, Doss was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

A word that often recurs when reading accounts of Doss's exploits is remarkable. What Doss did was remarkable, not only because of the physical and moral strength it took, or the courage to face such a murderous, often invisible enemy, but also because Doss was a pacifist. A Seventh-day Adventist, Doss had believed American involvement in World War II to be justified but would not himself take a human life. He had enlisted as a medic but been put into training with a rifle company, where he faced harassment and abuse for "cowardice."

The film

Andrew Garfield as Desmond Doss and Theresa Palmer as Dorothy Schutte in Hacksaw Ridge

Hacksaw Ridge began with another film: The Conscientious Objector, a documentary about Doss produced for the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Doss had, like another pacifist Medal of Honor winner, Alvin York, refused to market himself or his story for financial gain, and only agreed to do so much later in life. After seeing The Conscientious Objector, producer Bill Mechanic optioned Doss's story for a full Hollywood treatment. Doss would die, in 2006 at the age of 87, long before the project came to fruition.

Mechanic spent years developing Hacksaw Ridge. Major studios proved uninterested; even more than a decade ago, just before the advent of the Marvel series with Iron Man (2008), studios wanted properties with franchise potential. A film about a devoutly religious pacifist did not pique studio interest. Mechanic even approached Walden Media, which had produced the faith-inflected Narnia films in the early 2000s, but their insistence on "a soft PG-13" bothered Mechanic, whose interest in Doss's story stemmed precisely from the man's courage in horrible conditions.

Mechanic eventually brought Mel Gibson on to direct. This was an inspired choice. Similar to his biblical epic approach to Braveheart, Gibson brought an old Hollywood sensibility to Hacksaw Ridge and a famous—if not infamous—obsession with physicality and suffering to the second half of this picture.

The filmmakers—Gibson, Mechanic, and screenwriter Robert Schenkkan, who also worked on Tom Hanks's HBO miniseries The Pacific—structured Hacksaw Ridge in two acts rather than the traditional Syd Field three-act structure. The result is a bifurcated movie, radically different in tone and execution in its first and second halves. The first half is an old Hollywood love story that flirts with corniness. Schenkkan, in the behind-the-scenes features of the DVD, speaks of the challenge of making Doss, an atypical Hollywood hero, interesting: a man with deep personal faith, no vices, and a relationship with closely observed boundaries. I think Hacksaw Ridge succeeds at making Doss relatable and likable by embracing him and his world unironically and even lovingly. Doss's romance with Dorothy Schutte is (refreshingly, I have to say) chaste and old-fashioned, and even the abuse Doss suffers during bootcamp at the hands of his fellow recruits (all fun Hollywood "Central Casting" types) is squeaky clean, language wise. Only after a couple viewings did I realize how little swearing there is in the film.

Gibson carefully adopted this calm, reassuring, old fashioned aesthetic to create the maximum possible contrast between the world Doss leaves behind and the world he enters in the second act—Okinawa in 1945.

Hacksaw Ridge's Okinawa set on an Australian farm.

Shot on small, low-budget locations in Australia but with a panoply of skilled makeup and special effects artists, the film's combat scenes are harrowing. Despite watching dozens and dozens of war movies since I was a kid, Hacksaw Ridge shocked and disturbed me. The combat is extreme—over-the-top, frenetic, gory, ultraviolent, and indiscriminate—and the wounds inflicted on human flesh detailed, graphic, and severe. This treatment of combat—by the director of The Passion of the Christ, a fact seldom overlooked—has brought Hacksaw Ridge in for some criticism, the essence of which is the irony of a film about a pacifist being filled with such gruesome, in-your-face violence and gore. A few reviewers seem to think that Hacksaw Ridge glorifies war, and others seem repelled by the inferred glee they imagine Gibson takes in staging such scenes.

But like the near-cheesiness of the pre-war scenes, this violence serves a crucial purpose to the film and its pacifistic message. I cannot emphasize enough what a round-the-clock horror show Okinawa was. The combat lasted two and a half months and devastated the island, with around a quarter of a million people killed and wounded as a result. Mechanic rightly intuited that he could not do justice to Doss's story with a PG-13 version because Okinawa was not a PG-13 experience (compare how the PG-13 Unbroken pulled some of its punches in its depiction of Japanese POW camps). Doss's heroism—his refusal to carry a weapon (some medics are, accurately, shown carrying pistols and carbines in Hacksaw Ridge) despite the danger, and his repeated return to the killing zone—would not have registered on the gut, emotional level they did without a brutal depiction of what Doss was risking to save the lives of others. In addition, by the time Doss himself is wounded the injuries feel real because we have seen so much of what has happened to others before him.

Finally, Hacksaw Ridge's violence heightens the film's religious tones and iconography. (I think iconography is exactly the right word: witness that slow-motion shot of Doss washing the blood off after he comes down from the ridge.) I have plenty of differences with Doss's sect, but the courage he showed, the sheer physical punishment he took in sacrificing himself for others, and the love with which he did it show a man modeling Christ better than anything Hollywood could come up with. For that reason alone, Gibson, with his hyper-sacramental sense of the physicality of the world and what it demands of people, would have been the perfect choice to direct. I think the finished product speaks for itself.

The film as history

I'll be brief on this point. Hacksaw Ridge tells Doss's story, but it tells it in the way, again, of Old Hollywood. The film Hacksaw Ridge reminds me most of is Sergeant York, which hits many of the same beats and has a similar tone, structure, and hard-hitting violence (by 1941 standards). It also freely elides and condenses the events of Desmond Doss's life story.

You can find more detailed breakdowns of the liberties Hacksaw Ridge takes elsewhere (here's one good one), but a handful include:

Desmond Doss standing above the cargo nets on the Maeda Escarpment, 1945

Doss and Dorothy were already married by the time he enlisted, so he did not miss their wedding after being thrown into the brig.

Dorothy did not become a nurse until after the war and she did not meet Desmond at a hospital.

Tom Doss's alcoholism was exaggerated and the dispute over the pistol did not directly threaten Doss's mother.

Doss actually had experience as a combat medic on Guam (July and August 1944) and Leyte (October-December 1944) before landing on Okinawa.

Smitty, Doss's primary antagonist through bootcamp, was a composite character, as were most of the other members of Doss's unit.

The dramatic last-second intervention of Tom Doss at his son's court martial was invented; in reality, he phoned a member of the Seventh-day Adventist Church's leadership, who went through channels with the Pentagon and helped clear up Doss's situation.

What these liberties all have in common is that they were taken to condense and, especially, heighten the film. In the case of the cliffs Doss's unit must scale to reach Hacksaw Ridge proper, the heightening is literal. The one thing Gibson toned down was the nature of Doss's final wounds: after being blown up by a grenade, Doss gave up his stretcher for a more severely wounded man, had his left arm shattered by a bullet, splinted it himself, and crawled 300 yards to safety. That, Gibson thought, no one would believe.

I'm not particularly bothered by the film's effort to condense Doss's life. Reading the real story, it is diffuse and extremely complicated, and the filmmakers had to be selective in their presentation in order for the story to work in their medium. None of the changes compromise the story, I think, and all were calculated to set up and make intelligible Doss's actions on Okinawa (witness his nascent medical skill and interest in helping others illustrated by early scenes surrounding his meet cute with Dorothy).

Nor am I particularly bothered by the heightened tone and presentation of the film, since it is consistent all the way through. Hugo Weaving as Tom Doss isn't just a tormented alcoholic, he's a wildly tormented alcoholic. (Weaving skillfully brings his performance away from the verge of scenery-chewing several times, especially his dinner scene after Doss's brother enlists, and the pathos he evokes is both surprising and real.) Doss's tormentors don't just harass him, they physically pummel him. The violence is not just shocking and gruesome but operatic and balletic, and places a heavy emphasis on machine guns and hand to hand combat when much of the time the enemy fired invisibly from bunkers and caves. All of this is in the service of a legitimate interest in the story, and the exaggeration, I think, helps. To bring a relevant passage from Flannery O'Connor into it:

The novelist with Christian concerns will find in modern life distortions which are repugnant to him, and his problem will be to make these appear as distortions to an audience which is used to seeing them as natural; and he may well be forced to take ever more violent means to get his vision across to this hostile audience. When you can assume that your audience holds the same beliefs you do, you can relax a little and use more normal ways of talking to it; when you have to assume that it does not, then you have to make your vision apparent by shock—to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost blind you draw large and startling figures.

Despite his outward appearance, Desmond Doss was a large and startling figure and the storytelling suited him.

If I could change one thing about Hacksaw Ridge, it would be to emphasize what a longterm sacrifice Doss made on Okinawa. Shortly after the end of the war, Army doctors discovered he had tuberculosis, probably contracted in the Philippines, and he spent the next six years in and out of VA hospitals before being discharged with 90% disability. During the 1970s, an apparent overdose of antibiotics caused him to go completely deaf, requiring a cochlear implant years later. In all, Doss lost much of the use of his left arm, five ribs, a lung, and years of his life and health in the service of his fellow man.

How all of that could have been incorporated into the film, I don't know, but I'm glad his story has gotten so much attention and hope it will inspire future Desmond Dosses.

More if you're interested

Doss was surprised with an appearance on This is Your Life in 1959; the entire episode is available on YouTube here. Doss's genuine humility and discomfort at the attention he's been given are palpable. Doss's company and regimental commanders, both of whom were portrayed in the film, also appear on the show.

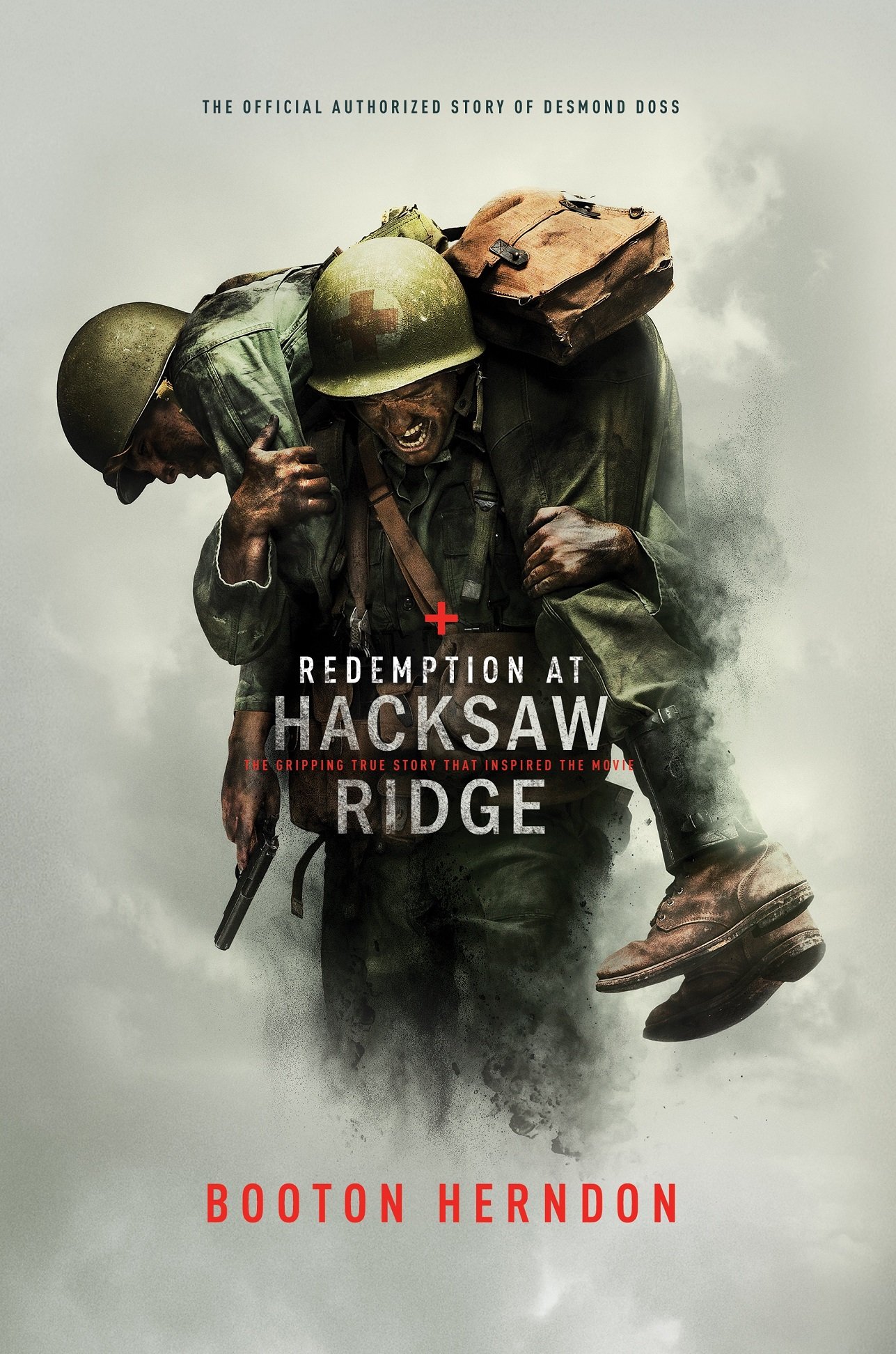

Doss's life story has been told by Booton Herndon in The Unlikeliest Hero. The Seventh-day Adventist Church reprinted Herndon's book and gave away thousands of copies when the film came out. There are two versions: Redemption at Hacksaw Ridge, which is updated with photos and Doss's life after the war, and Hero of Hacksaw Ridge, an abridgement. The Conscientious Objector, the documentary that led to the production of this film, is available on DVD and on YouTube.

Okinawa: The Last Battle, cited above, has a good chapter on the events surrounding Doss's exploits available for free from the US Army Center for Military History. Richard B. Frank's Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire has a good assessment of Okinawa in its context as a stepping stone to the invasion of Japan, and Max Hastings's Retribution: The Battle for Japan, 1944-45 has a good chapter on Okinawa. Robert Leckie, Marine veteran of Guadalcanal, New Britain, and Peleliu, wrote a readable popular history of the battle called Okinawa: The Last Battle of World War II.

The indispensable book on Okinawa, if you want to understand the horror that men like Doss lived through, is the aforementioned Eugene Sledge's memoir With the Old Breed. This book is a must-read for anyone who has a rosy or triumphalist view of war.

Next week

I haven't settled on a film for next week just yet, but a kind colleague of mine just dropped off a foreign film I've wanted to see since high school, so it may be that. Until then, thanks for reading!