Kingdom of Heaven

/This week's Historical Movie Monday looks at another old medieval favorite that has serious historical problems. Like Braveheart, it throws accuracy to the winds. Unlike Braveheart, it is too cold, cerebral, and present-minded to make the sacrifice worthwhile. The film is Ridley Scott's Kingdom of Heaven.

“Be without fear in the face of your enemies. Be brave and upright, that God may love thee. Speak the truth always, even if it leads to your death. Safeguard the helpless and do no wrong; that is your oath.”

The history

Following the fall of Jerusalem to the knights of the First Crusade in 1099, the kingdoms and counties founded to safeguard Christian holy sites in the Near East faced ongoing problems. The disorganized, underfed, disease-ridden knights' miraculous success, it became clear, had been aided by division within the Islamic world. The first crusaders had launched their pilgrimage (their word: the word Crusade was not applied until much later) at a time when the Seljuq Empire was subdivided among numerous rival lords, and the Seljuqs themselves warred off and on with the Fatimid caliphate in Egypt. Over the course of the next century, the Islamic empires of the Near East attained first equilibrium and finally cohesion thanks to a number of powerful, charismatic warlords. Among these were Zengi, Nur ad-Din, and, finally, Saladin.

With Saladin, the situation in the east was reversed. The fractious European guardians of Jerusalem now faced a determined and unified opponent and the Crusader kingdoms began to fall. Appeals for reinforcements from the West provoked little response. The king of Jerusalem and his lords had to rely heavily on diplomacy to maintain their control, and when it came to blows a new phenomenon, the military orders, took on a large share of the burden. These orders, the two most powerful of which were the Knights Templar and the Knights Hospitaller, combined the traditional vows of monks with the emerging chivalric ideals of knights.

Orlando Bloom and David Thewlis in Kingdom of Heaven.

In 1185, Baldwin IV, King of Jerusalem, died aged 24. He left the throne to his eight-year old nephew Baldwin V. But the boy king died a year later, and the throne passed, with some controversy, to the boy's mother, Sibylla. Among those debating the succession was Balian of Ibelin, whose stepdaughter Isabella had a better claim to the throne, and Reynald of Châtillon, Prince of Antioch, who supported Sibylla. At Sibylla's coronation, she brought forward her husband Guy of Lusignan to be crowned and share power with her.

Sibylla and Guy were a disaster. In less than a year, in July 1187, Guy had led his armies against the threatening army of Saladin and into a trap. Cut off from their route of escape and with no water supply in the torturous summer heat, Guy's army was forced into combat with Saladin at Hattin and annihilated. Guy, and much of the Crusader kingdoms' nobility with him, was captured. Saladin's forces ritually massacred their Templar and Hospitaller prisoners. Reynald, a longtime troublemaker for Saladin, was killed by Saladin himself. Jerusalem lay open to attack.

Now bereft of its king, Jerusalem turned to the leadership of Balian, who had passed through Muslim-controlled territory to the city to rescue his wife and family. At the request of Queen Sibylla, Balian took command and refused to capitulate to Saladin.

During a siege lasting just under two weeks, Saladin's engineers pounded the city walls with trebuchets and other siege engines, undermined another portion of the walls, and repeatedly attacked, though without success. Finally, on October 2, Balian agreed to negotiate terms with Saladin and surrendered the city. The city's inhabitants and the numerous refugees who had fled Saladin were allowed to leave—if they paid a ransom. Not all could.

The fall of Jerusalem in 1187 galvanized the Latin Church and Western Europe responded with another upsurge of Crusade, this time led by three of the most powerful men in Europe—Frederick Barbarossa, Holy Roman Emperor; Philip Augustus, King of France; and Richard the Lionheart, King of England. This crusade, too, gradually fell apart, and while Richard was able to negotiate safe passage to Jerusalem for Christian pilgrims, he could not retake the city.

The film

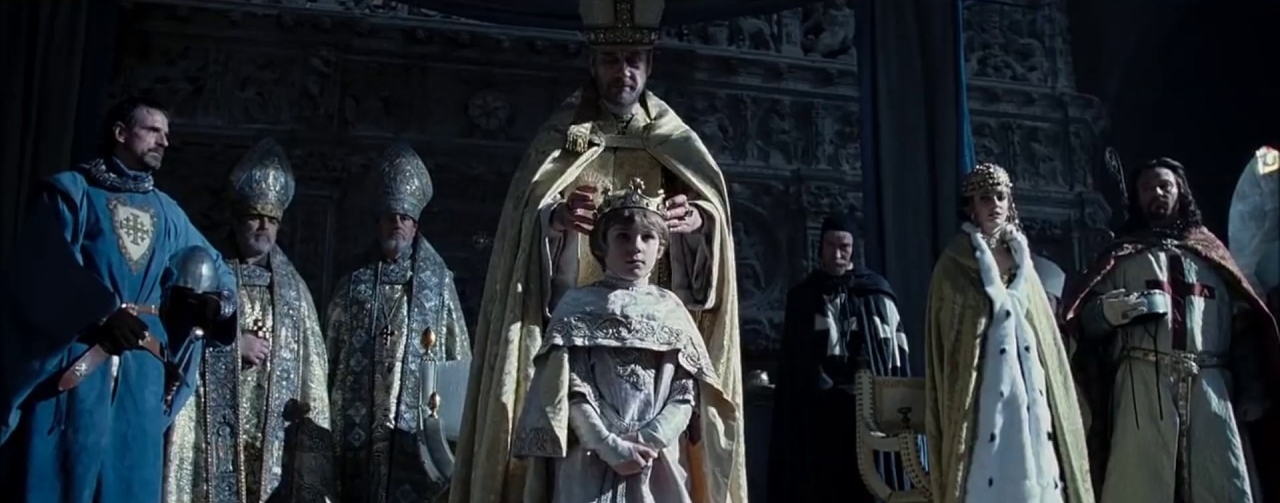

The coronation of King Baldwin V of Jerusalem in Kingdom of Heaven. Tiberias (Jeremy Irons), Sibylla (Eva Green), and Guy of Lusignan (Marton Csokas) look on.

Based on a script by William Monahan (screenwriter for The Departed), Kingdom of Heaven follows the course of actual history in broad outline while having some serious, fundamental problems with that history, about which more below.

The film's director, Ridley Scott, is one of the few "visionary directors" so frequently advertised in trailers nowadays who may actually deserve the title. His films are always visually stunning, and Kingdom of Heaven is no exception. Shot on film by frequent collaborator John Mathieson, who had first worked with Scott on Gladiator, this film looks great from beginning to end. Production designer Arthur Max, who had also worked on Gladiator, enhanced numerous preexisting Spanish locations with set dressing and props to give the film a palpable real-world sensibility. Scott himself strove to make the film feel authentic, inventing minor details for background action like a method for cleaning and polishing mail and making the combat as intense, violent, and frightening as possible. Kingdom of Heaven has stunning location photography, beautiful lighting, gorgeous costumes, and thrilling battle scenes. One reason I enjoy it is because it's not only beautiful to look at, but the sheer amount of detail makes the film feel like it takes place in a big, real world rather than a series of sets.

Eva Green as Sibylla

I emphasize the visual splendor of Kingdom of Heaven for a reason. Like Braveheart, which is a useful point of comparison, Kingdom of Heaven revels in big-budget, widescreen glory meant to evoke the epics of the 1950s and 60s. This plays to Scott's strengths as a visual filmmaker and storyteller. Unfortunately, the casting and acting and the performances—all of which helped sell Braveheart despite its historical flimflam—don't measure up, and the result is that this beautiful film is often dramatically inert.

Acquitting themselves well are Liam Neeson as Godfrey, Balian's father; Jeremy Irons as a composite character, a stalwart veteran named Tiberias; and Eva Green, who plays Sibylla as an emotionally damaged seductress and a Westerner slowly going native in the Levant. David Thewlis has an excellent turn as an unnamed Hospitaller, who may or may not be a guardian angel for Balian. Thewlis is, with Neeson, the most sympathetic character in the film. Edward Norton deserves special mention for his performance as the leper king Baldwin IV; he never once removes an eerily expressionless mask and nevertheless gives a magnetic performance.

Lesser performances come from Marton Csokas and Brendan Gleeson as Guy and Reynald, who are obviously meant to be the film's villains. I say "obviously" because their performances are histrionic mustache-twirling of silent film caliber—Csoka's Guy skulks and sneers and insinuates as if he had the words Bad Guy emblazoned on his forehead, and it seems like the usually wonderful Gleeson is just seeing what he can get away with, playing Reynald as an ultraviolent loon.

The film's biggest problem, performance-wise, is Orlando Bloom as Balian. Bloom had previously worked with Scott in Black Hawk Down—his character spent the majority of the film in a coma—but he is woefully miscast here, and out of his depth. His Balian is supposed to be a thoughtful, intelligent, but practical man who is new to the ways of the world and struggles with doubt and regret. Bloom works his hardest but most often looks confused. He is overpowered by the other performers in virtually every scene, especially Neeson, Norton, and his intended love interest, Green.

But Bloom was not Kingdom of Heaven's only problem. The film was cut down by over an hour for its theatrical release, turning some scenes into detached nonsense and excising the coronation and early death of Baldwin V completely. The pacing, despite Scott's best efforts to meet the studio's demand for a shorter film, was awkward, at best. I remember watching Kingdom of Heaven in theaters and feeling that the film lurched along, with dramatic shifts in tone and character motivation, especially Sibylla, who seemed to have a mental breakdown for no reason. As a result, reviews ranged from "meh" to negative and the film, while not a bomb, was not a financial success.

Fortunately, Scott was able to get his "preferred version" out on DVD, and the director's cut is an immensely improved film.

The film as history

Marton Csokas as Guy of Lusignan, inaccurately depicted as a Knight Templar in Kingdom of Heaven

As soon as the film begins, before we have even seen the first shot, we're in trouble. The film opens with this series of titles:

It is almost 100 years since Christian armies from Europe seized Jerusalem.

Jerusalem fell to storm in 1099. The film opens in a fictional scenario in the mid-1180s. Close enough.

Europe suffers in the grip of repression and poverty. Peasant and lord alike flee to the Holy Land in search of fortune or salvation.

The "dark ages" stereotype right out of the gate. One might ask Repression by whose standard? or Poverty by whose standard? Europe was actually doing fairly well in the 12th century: harvests were consistently good, the population was rising, literature and the arts flourished, and the seed of the university—which often encouraged more debate and academic freedom than their modern counterparts—had taken root.

Furthermore, this title shows the film's fundamental misunderstanding of the Crusades as essentially colonial projects. For the vast majority of Latin Christians, the Holy Land was a pilgrimage destination. The Crusader kingdoms had endemic and ongoing problems manning their own defenses, since crusading knights would fulfill their vow to go to Jerusalem and immediately return home to sort out the problems that had inevitably arisen in their absence (best example: Richard the Lionheart). The Crusades-as-colonialism narrative has been so thoroughly debunked by the work of historians like Jonathan Riley-Smith and many, many others that is is laughable to see it dramatized this way. But there are reasons it is so.

Finally:

One knight returns home in search of his son.

This sets up the film's entirely artificial backstory for Balian, and off we go.

Kingdom of Heaven was not a hit with Crusade historians. Riley-Smith lamented that "at a time of inter-faith tension, nonsense like this will only reinforce existing myths." I happen to agree. Thomas F. Madden wrote that

Ridley Scott has repeatedly said that this movie is “not a documentary” but a “story based on history.” The problem is that the story is poor and the history is worse. Based on media interviews, [the filmmakers] clearly believe that their story can help bring peace to the world today. Lasting peace, though, would be better served by candidly facing the truths of our shared past, however politically incorrect those might be.

It is difficult to enumerate the historical failings of Kingdom of Heaven because there are so many on every level of historical representation, from misinterpretation of motives and character, the ordering of events, and the roles played by particular people, to quibbles about anachronistic costuming. But some of the film's historical problems are more serious than others, and those fundamental problems are the cause of most of the others.

While most of the film's characters are real people, the film plays fast and loose with their respective characters. Balian's origins are well known and unremarkable. He was not the illegitimate son of a nobleman and was not a proto-Zen modern secularist. Far from it—at one point of the siege of Jerusalem he threatened to kill Muslim hostages. He was also present at the Battle of Hattin rather than mooning around in Jerusalem. King Baldwin was a leper and did attempt to maintain the peace, but this had more to do with the ever tenuous and fragile state of his undermanned kingdom than abstract Enlightenment principle. While most of the Christian characters are exaggerated for effect, Saladin's character is substantially softened to make him more palatable to moderns. Those who could not pay the heavy ransom he imposed on Jerusalem were sold into slavery, and he personally participated in the massacres of prisoners after Hattin and the siege of Acre.

Brendan Gleeson hamming it up as Reynald

The film goes out of its way to villainize its bad guys. Scott really lays it on thick. Guy of Lusignan and Reynald of Châtillon are inaccurately depicted as Templars, presumably because some members of the audience will have heard of the Templars and have a vaguely negative impression of them. This is an especially egregious error since Guy is depicted (accurately) as married, something the warrior monks of the Knights Templar were forbidden to do. The real Reynald was also married; the filmmakers seem to have conflated him with the Templars' Grand Master, Gerard of Ridefort, for no apparent reason, and to have added insult to injury by portraying him as insane.

One could look past some of these problems were it not for Kingdom of Heaven's greatest failing—it is not interested in the past for its own sake.

In a series of blog posts from two years ago (Part 1 and Part 2), around the time of Free State of Jones's release, historian Chris Gehrz outlined four useful questions to ask of films that purport to tell us stories from history:

Is it entertaining?

Is it truthful?

Is it actually interested in the past?

Does it prompt the audience to engage in historical thinking?

The only one of these questions to which I would answer Yes, in regard to Kingdom of Heaven, is the first—and even then, with Orlando Bloom a black hole of charisma at the center of the film, that Yes would be equivocal.

As to whether Kingdom of Heaven is truthful, the answer must be No. Gehrz quotes the novelist E.L. Doctorow: "The historian will tell you what happened. The novelist will tell you what it felt like." This, I think, is the crucial difference between Kingdom of Heaven and the otherwise historically atrocious Braveheart. For all its flaws, Braveheart conveyed some sense of the spirit of that time; Kingdom of Heaven is, by Ridley Scott's own admission, so relativized and altered to make sense to modern people in modern terms, that it fails in its attempt to transport viewers to the 12th century.

“Kingdom of Heaven . . . is relentlessly present-minded.”

This brings me to Gehrz's third and fourth questions. I think Ridley Scott may be interested in the past—he has certainly made a lot of historical movies, beginning with his feature debut—but his films aren't. Put another way, he is so consumed with finding a usable past for his personal messages that he does violence to history in order to fit it to the Procrustean bed of modern film.

Kingdom of Heaven—arriving at the height of Post-9/11 political upheaval, media agony over the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, and alternating accusations of Islamophobia and capitulation to Islamism—is relentlessly present-minded. (Some reviewers saw this as a strength.) Its characters are stand-ins for, on one side, right-wing hawks, depicted here as bloody-minded religious fanatics (a recognizable stereotype for anyone who lived through that time); their opponents are noble foreigners with legitimate grievances rooted in colonialism and Western oppression, creatures of the Orientalism texts of late-20th century grad schools; and caught in the middle are the open-minded, sensible, spiritual but not religious types who have somehow discovered Enlightenment-era ideals of religious toleration in the 1180s. Scott also packs in some meditations on class, equality, nobility, honor, and chivalry, but always with an eye to tickling modern sensibilities.

Witness this scene: Balian, Scott's agnostic modern hero, threatens to destroy Jerusalem while negotiating with Saladin:

Saladin: Will you yield the city?

Balian: Before I lose it, I will burn it to the ground. Your holy places—ours. Every last thing in Jerusalem that drives men mad.

In Scott's vision, religion, especially religious fanaticism (that is, anyone taking religion more seriously than I do) is the problem. By choosing the 12th century to purvey this message, he has plenty of straw men to joust with.

While Kingdom of Heaven looks great, has mostly wonderful sets and costumes, and loads of brilliantly staged action, its characters and setting are not authentically 12th-century, but puppets in a miniature theater acting out a feebly articulated morality play about religion, terrorism, Western guilt, and foreign policy. Which is a shame, because the real story is so interesting on its own.

More if you're interested

The historical literature on the Crusades is huge, and somewhat unusual in that you're best served by looking at the more recent work rather than the older stuff. Past Crusade history was often inflected with anti-Catholicism, the Romanticism of Sir Walter Scott, or Marxist theory, the latter deeply enough to have persisted in the popular imagination (and influenced Kingdom of Heaven). Fortunately, the last two generations of Crusade historians have amended, nuanced, or outright debunked a lot of old conceptions of the Crusades.

The best one-stop book if you're looking to an accessible introduction is The Concise History of the Crusades, by Thomas F. Madden, now in a third edition. Madden offers a short, well-researched, and well-written narrative of the Crusade movement with good analysis of what the Crusades were (always a vexed question, especially since the Crusaders themselves didn't use the word), why the Crusading movement emerged where and when it did, and how it changed over time. He also, like many historians since 9/11, includes helpful discussion of Crusading's legacy. Oxford UP's Very Short Introductions series also has a slim little volume on the Crusades by Christopher Tyerman.

Other good surveys of the time and movement include The Crusades: The Authoritative History of the War for the Holy Land, by Thomas Asbridge; Holy Warriors: A Modern History of the Crusades, by Jonathan Phillips; and God's War: A New History of the Crusades, by Christopher Tyerman. Dan Jones's recent book The Templars: The Rise and Spectacular Fall of God's Holy Warriors, also covers many of the events of this film.

The work of Jonathan Riley-Smith must not be overlooked. Riley-Smith helped demolish many theories of what caused the Crusades through intensive research of Crusader wills, which demonstrated that 1) Crusaders planned to return from rather than stay in the Holy Land, 2) they were predominantly the heads of households or the heirs of great fortunes, men with the most to lose from a failed pilgrimage, and 3) going on Crusade was ruinously expensive, and Crusaders, if they took the cross out of a profit motive, would have been better off staying home. Riley-Smith's book The Crusades: A History is a good one-volume history of the period and an introduction to his work.

Two good references for medieval warfare in this period are Medieval Warfare: A History, an indispensable anthology edited by Maurice Keen, the great historian of medieval chivalry; and Western Warfare in the Age of the Crusades, 1000-1300, by John France. Norman Housley's Fighting for the Cross: Crusading to the Holy Land, also offers a lot of good insight into the lived experience of the Crusaders.

One of the best resources for serious engagement with the history, historiography, and myths of the Crusades is Seven Myths of the Crusades, Alfred J. Andrea and Andrew Holt, Eds., the first of a new series from Hackett Publishing. This short, well-researched collection of essays tackles some of the most well-known and persistent myths of the Crusades, including the myth of pure Western Christian aggression, the Children's Crusade, the Marxist myth of Crusaders as colonialists, Templar and Mason conspiracy theories, and the notion that present day Islamic terror stems from "a nine hundred-year-long grievance" with the West. It's excellent.

Next week

In an unusual occurrence, Easter falls on April Fool's Day this year. The same was true in 1945, when April 1 served as D-day for the Allied landings on Okinawa. To commemorate the battle, we'll look at a recent film about an unusual participant, conscientious objector Desmond Doss. The film: Hacksaw Ridge.

Thanks for reading!