A Man for All Seasons

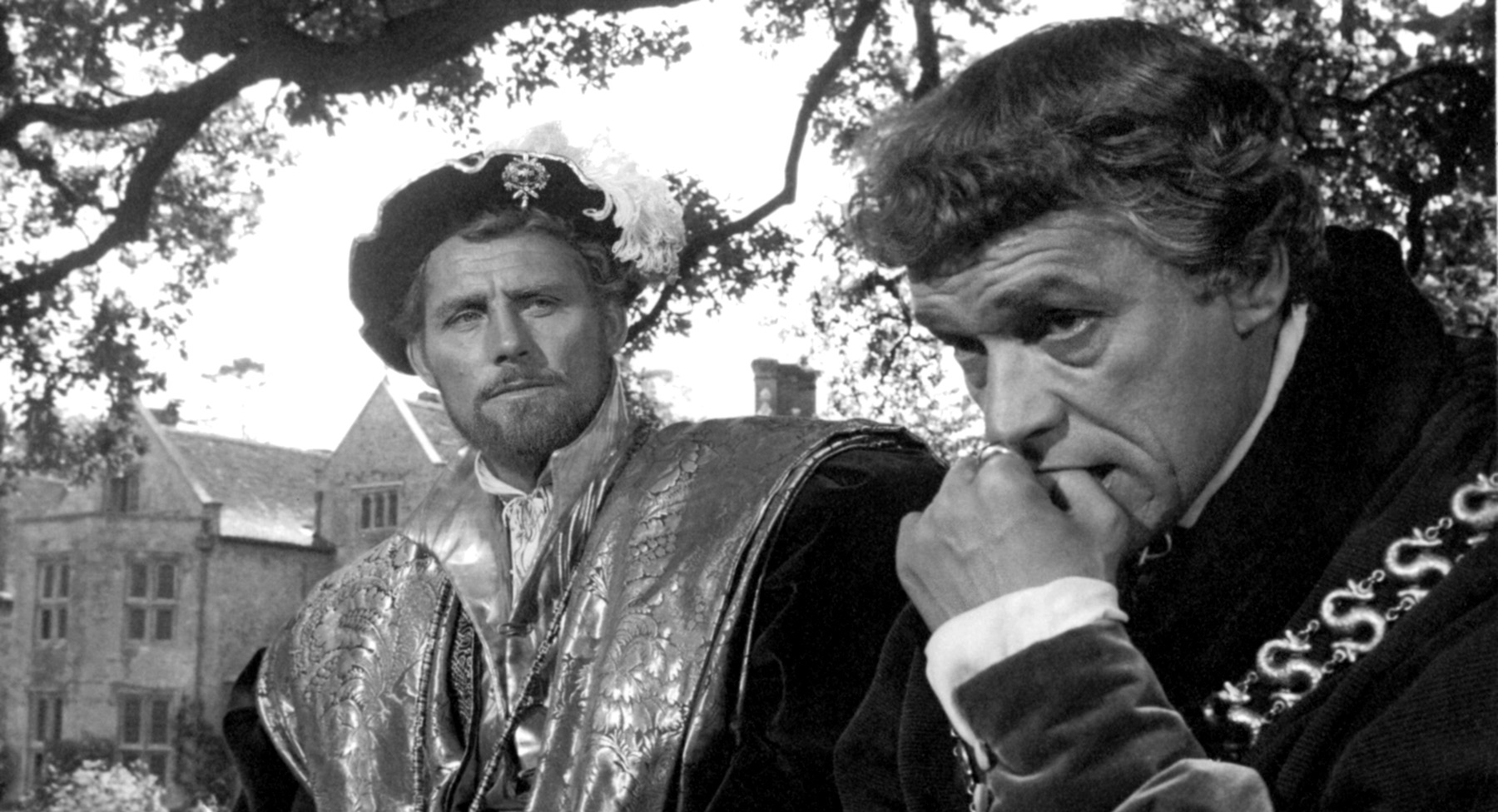

/Robert Shaw as King Henry VIII and Paul Scofield as St. Thomas More in A Man for All Seasons

St. Thomas More's birthday was last week, and this provided me with an excuse to inaugurate a new, semi-regular feature for this blog: Historical Movie Monday. This week, I write about a favorite of mine, a film I happened to be rewatching as More's birthday rolled around: A Man for All Seasons.

“I am commanded by the King to be brief, and since I am the King's obedient subject, brief I will be. I die his Majesty's good servant, but God's first.”

The history

A Man for All Seasons is the story of Sir Thomas More, a London lawyer, writer, philosopher, and renaissance humanist scholar. After the Archbishop of Canterbury helped him get into Oxford, More became a lawyer and statesman, worked for Cardinal Wolsey, the Lord High Chancellor, and communicated with some of the greatest humanist scholars of his time, including Erasmus, compiler of the Textus Receptus, the first critical edition of the Greek New Testament. Erasmus even stayed with More and his family when he visited London. They entertained themselves by translating Lucian together.

More was well-educated, intelligent, a man of wide experience, a prolific writer, and dedicated to his family and, above all, to his faith. He personally oversaw the education of his children. This included, atypically for the time, his three daughters, the eldest of whom, Margaret, became famous for her intelligence and command of Greek and Latin. He was also a good-humored wit. According to Erasmus, "from earliest childhood [he had] such a passion for jokes, that one might almost suppose he had been born for them." His sense of humor comes out most clearly in Utopia, published in 1516—in which he describes an outlandish society meant to satirize the Europe of his day—and, perhaps, in his death.

Sir Thomas More, by Hans Holbein the Younger

More traveled often with Cardinal Wolsey on diplomatic missions to the continent. He eventually became a secretary to King Henry VIII himself, and in 1529, with Wolsey dying and out of Henry's favor, he became the first layman to serve as Lord High Chancellor, a position he held for two and a half years before resigning.

More was a slightly older contemporary of Martin Luther, and the schism within the Catholic Church that resulted from Luther's 95 Theses defined the later part of his career. He wrote on numerous theological and philosophical topics and conducted literary debates with Luther and William Tyndale. As Lord High Chancellor, he was charged with prosecuting heretics in Henry's kingdom. While the Protestant propagandist John Foxe's accusations that More tortured prisoners not only in the Tower of London and but in his own home are false, More did preside over numerous heresy trials, six of which resulted in the condemned being burned at the stake.

It is against this background that the final crisis of More's career played out. When Henry, who had earned the title Defender of the Faith from the pope for his sparring with Luther over the sacraments, became convinced that his wife Catherine could not bear him a son, he had a sudden change of mind about the sacrament of marriage. Henry had worked with Cardinal Wolsey to get an annulment from the pope on the grounds that Catherine had previously been married to Henry's elder brother Arthur. The marriage was therefore incestuous according to canon law, and had only been permitted with a special dispensation from a previous pope. Henry hoped that this, with Wolsey's intercession, would allow him to weasel out of his 24-year marriage and allow him to marry his mistress, Anne Boleyn.

Every attempt by Henry to gain an annulment failed. More, Wolsey's replacement as Lord High Chancellor, refused to cooperate, as the Church's teaching and laws were clear on the matter. Nevertheless, beginning in 1532, Henry pushed forward a series of parliamentary acts that separated the English church from the Catholic Church, made Henry the head of the Church of England, declared his children by his new wife his legitimate heirs (cruelly cutting off his one surviving child by Catherine, Mary), required a loyalty oath on all of these matters, and set a penalty of death for anyone who refused. Early on in this series of acts, More resigned.

“Thomas More, who seemed sometimes like an Epicurean under Augustus, died the death of a saint under Diocletian. He died gloriously jesting.”

More had too high a profile to ignore, even though he refused both to take the oath and to denounce it. Enemies, including Henry's enforcer, Thomas Cromwell, and Richard Rich, an ambitious young courtier, conspired against him, accusing him of a variety of crimes but the charges didn't stick. Henry's ministers eventually forced the issue, interrogating More several times, ordering him repeatedly to swear the oath of loyalty, and imprisoning him in the Tower of London. At his brief trial on July 1, 1535, perjured evidence was used to convict him of treason, and the court sentenced him to death.

More was beheaded five days later. According to witnesses, he joked on his way up the scaffold.

The film

A Man for All Seasons is a film adaptation of a critically acclaimed play by Robert Bolt, who had previously scripted Lawrence of Arabia and would later write The Mission. Bolt adapted the play for film himself, and the film was directed by Fred Zinnemann, director of critical favorites High Noon and From Here to Eternity.

Paul Scofield as Sir Thomas More on trial

Zinnemann's High Noon offers interesting points of comparison. Like that film, A Man for All Seasons pits a principled authority figure against a seemingly unstoppable opponent. The hopelessness of his situation causes even those nearest him to waver and withdraw their support, and he faces the ultimate threat alone. Unlike Marshal Will Kane, Sir Thomas More gives up his authority as part of his resistance, fights back with words and reason, and—at least to the purely pragmatic eye—loses. A Man for All Seasons dramatizes a resistance to tyranny that does not rely on meeting force with force.

The sets, locations, costumes, and cinematography are beautiful. Scenes of the natural beauty of the Thames—always associated in the film with More against the crenelations and gargoyles paired with Henry and his yes-men—are particularly striking. The film came out in 1966, during an awkward transition from the stagy interior set design of the 1950s to the harder realism of the 1970s. It's perfectly poised between the two; the locations in the film feel real, even the sets, and at least a few scenes were shot in period-authentic locations. The trial scene was supposedly shot in Westminster Hall, where More was actually tried, but I haven't been able to confirm that.

The performances are uniformly excellent. Robert Shaw, in a supporting role, is a young, energetic Henry VIII whose tyrannical inclinations are barely contained at the beginning of the film. "He is no caricature," Alison Weir writes, "but an attractive, intelligent man whose every whim has hitherto been gratified." Susannah York plays a charmingly erudite and devoted Margaret More, the only one of More's children depicted. You feel and believe the affection between More and his daughter, which raises the stakes in the final act. An obese Orson Welles is very good in a handful of scenes as Wolsey, ill and world-weary. Leo McKern is a bluff and formidably cutthroat Cromwell, and a very young John Hurt plays Richard Rich as an object lesson in virtue ethics. Rich begins the film an ambitious young man, begging More for preferment, and proves willing to debase himself further and further in his quest for position and recognition.

The standout performance is, of course, Paul Scofield as More. Scofield originated the role on stage, and he fully inhabits the part on film. It's a finely tuned, subtle performance, built out of minute gestures, flickers of emotion in his eyes, and the carefully controlled intonation of every syllable of his speech. It helps that he's working from a magnificent script, with wonderful dialogue and speeches, but without Scofield More could come across as a tedious scold or an out of touch fanatic. There are, indeed, elements of both in other depictions of More.

There's not a careless moment in the film—technically, artistically, or in the performances—and Scofield is its centerpiece.

The film as history

A Man for All Seasons covers approximately six years of More's life, from just before his appointment as Henry's Lord High Chancellor to the moment of his death. For a two-hour film with a limited cast of characters, A Man for All Seasons does remarkable justice to the complexity of the political and religious situation of the time and remains extraordinarily faithful to the facts. Luther lurks in the background—Will Roper, Margaret's suitor and eventual husband, is shown with a boyish enthusiasm for Lutheran doctrine—and this seemingly arcane theological issue finally erupts in the person of the king.

“It profits a man nothing to give his soul for the whole world... but for Wales, Richard?”

The film's characterizations of More and others are very good. One must allow for artistic license, but nothing in A Man for All Seasons cuts against the record. More really was keen-witted, eloquent, and with a savage wit; Henry really was full of bustle and machismo at this stage of his life; Cromwell really was Henry's cynical hatchet man; Rich really was a slave to his own ambition. Again, More is the best character in the piece, and he has all the best lines—especially his one-liners, like his celebrated zinger to the perjured Rich—but the film's depictions all ring true.

The trial and sentencing hew very close to the record. Peter Ackroyd, in his biography of More, reprints the entire transcript. You can read it in about ten minutes. Most of the changes Bolt makes to the trial are in the interests of streamlining, saving screentime, and simply updating the 16th century English for modern audiences. Even More's last words, spoken moments before his beheading, are taken essentially verbatim from the historical record. Only the jokes—as he ascended the rickety scaffold, the ailing More asked someone to help him up and promised to shift for himself on the trip back down—are omitted.

One man faces the power of the state.

One could nitpick, something More, a lawyer, would probably enjoy. There's no solid evidence that Henry VIII died of syphilis (see below). And it is not entirely true that More was silent. He refused to take the oath, but during these years he produced a constant stream of writing that, while never naming Henry or Anne Boleyn or directly addressing the controversy, clearly critiqued it. But the play does depict a larger truth about conscience and state power. As Paul Turner writes in his introduction to Utopia:

in Tudor England there was no freedom of speech; there was not even freedom of thought. More himself was executed not for anything that he had said or done, but for private opinions which he had resolutely kept to himself. It was not enough to abstain from comment on Henry VIII's astonishing metamorphosis into Supreme Head of the Church: More's very silence was a political crime.

How much more should these these events trouble us in a democratic age? Instead of the conflict of one's conscience with the will of a monarch, one now, in order to obey God or the dictates of conscience, must go against the majority. We've given up trying to please a king for trying to please everyone. It's a question More would have us consider, and seriously.

The film concludes with the narrator describing the fates of the major players:

Thomas More's head was stuck on Traitors' Gate for a month, then his daughter, Margaret, removed it and kept it till her death. Cromwell was beheaded for high treason five years after More. The archbishop was burned at the stake. The Duke of Norfolk should have been executed for high treason, but the king died of syphilis the night before. Richard Rich became chancellor of England and died in his bed.

That final sentence, which tells the audience that the film's scummy young striver lived a life of position and success, is the film's stinger, and masterfully brings one of the story's latent themes to the fore. Unlike High Noon's Will Kane, who does defeat his enemies in physical combat and does restore his reputation and standing and his relationship with his love interest—and then rejects everything but his love in disgust—More models a success of conscience. He is physically and materially defeated, stripped of rank and property, separated from his wife and children, and finally killed. And yet he succeeds, because faith, conscience, and truth are more important than the kind of success so eagerly grasped after by Henry, Cromwell, or Rich. And longer lasting.

A Man for All Seasons is a story we always need, perhaps especially now.

More if you're interested

My DVD of A Man for All Seasons includes this 18-minute Life of Saint Thomas More documentary. This short features a number of prominent historians and biographers, including John Guy and Alison Weir (see below). It's worth the time to watch for a capsule summary of the real More with reference to the film.

Peter Ackroyd's biography The Life of Thomas More is highly recommended as both well-researched and readable. It's also still widely available and easy to find. Tudors, the second volume in his ongoing multi-volume history of England, also covers the controversies surrounding Henry's divorce, remarriage, and Act of Surpremacy succinctly but with good detail in a readable narrative.

Historian John Guy has a number of books you might consult. First is Thomas More, which attempts to separate the man from the legend. Guy's entry in the Penguin Monarchs series, Henry VIII: The Quest for Fame, is a very short, readable biography of More's king, with good attention given to Henry's divorce, his split with the Church, and his eradication of dissenters, including More. Guy has also written The Tudors, part of Oxford UP's Very Short Introductions series.

Alison Weir, who has done a great deal to popularize the Tudors with her voluminous biographies, covers More well in Henry VIII: The King and His Court. Recent paperback editions include a short essay in which she compares various film depictions of Henry and his life.

Charlton Heston played More in a TV adaptation of A Man for All Seasons, which I haven't seen. Neither have I seen his portrayal by Jeremy Northam in The Tudors, which I gather is sympathetic but inaccurate. I have seen the BBC's Wolf Hall, based on the novel by Hilary Mantel, in which More is played by Anton Lesser opposite Mark Rylance as Cromwell and Damian Lewis as Henry VIII. Mantel is violently anti-Catholic and Wolf Hall is an admitted attempt to tear down More's reputation. I haven't read the novel, but I understand the miniseries to have toned down her attack, even if it includes Foxe's false accusations of torture. More comes across as an educated doofus, a man stupidly committed to principle instead of expedience (Cromwell, throughout, is held up as his pragmatic opposite). I still recommend Wolf Hall because it's excellent storytelling and filmmaking, but understand that its depiction of More is overtly hostile.

And of course there are the works of More himself. Utopia is readily available in a variety of editions and translations. I'm currently reading Paul Turner's translation for Penguin Classics. Vintage Spiritual Classics offers a modest Selected Writings anthology. Other works are readily available elsewhere, including free digitized texts online at places like Project Gutenberg. Check out More's Dialogue Comfort Against Tribulation, written while More awaited his death in the Tower.